5,300-year-old “bow drill” rewrites the story of ancient Egyptian tools

Researchers at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom and the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna have reexamined a small copper-alloy object excavated about a century ago from a cemetery at Badari in Upper Egypt. The new analysis indicates that the artifact may be the earliest identified rotary metal drill from ancient Egypt, dating to the Predynastic period (late fourth millennium BCE), before the rule of the first pharaohs began.

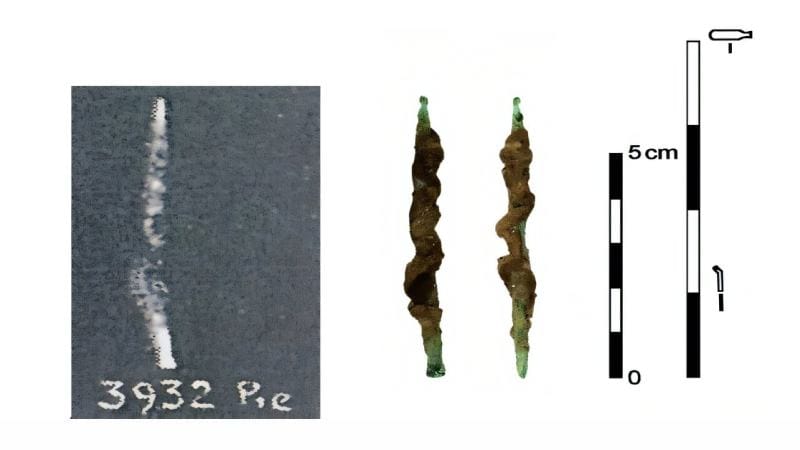

The object, catalogued as 1924.948 A at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, was found in Tomb 3932, which belonged to an adult man. When it was first described in the 1920s, the item — measuring just 63 millimeters in length and weighing about 1.5 grams — was classified as “a small copper piercer, with a leather cord wrapped around it.” The brief description led the artifact to receive little attention in the decades that followed.

In a new magnified analysis, researchers identified wear marks consistent with rotary drilling. Evidence includes fine striations, rounded edges, and a slight curvature at the working end of the tool — features associated with rotational motion rather than simple pressure-based hand piercing.

The study, published in the journal Egypt and the Levant, also describes six turns of an extremely fragile leather cord preserved on the object. According to the authors, this is possibly a remnant of the string from a bow drill — an ancient mechanism comparable to a hand drill, in which a cord wrapped around a shaft is moved back and forth with a bow, causing the drill bit to spin rapidly.

According to Martin Odler, lead author of the study and a visiting researcher at the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at Newcastle University, tools such as this drill were essential for everyday activities, including the production of furniture and ornaments. He states that the reanalysis suggests Egyptian craftspeople mastered reliable rotary drilling techniques more than two thousand years before the better-preserved drill sets previously known.

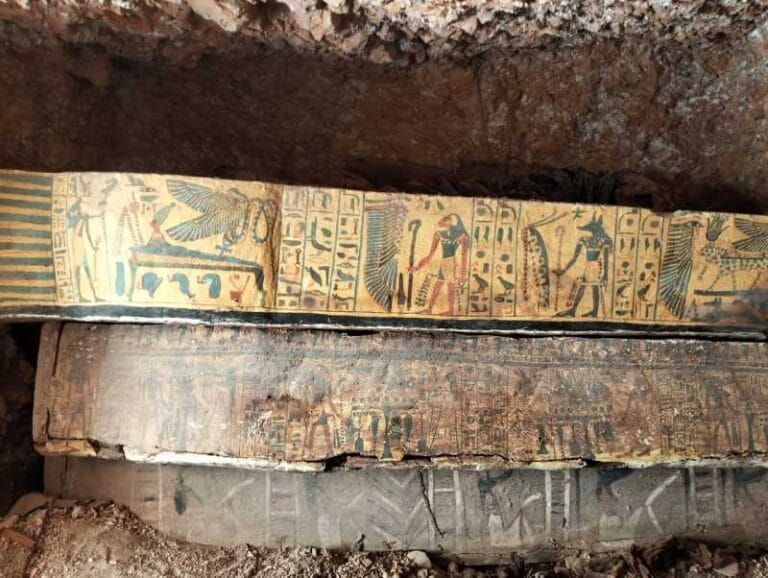

Bow drills are known from later periods of Egyptian history, including examples from the New Kingdom (second millennium BCE). Tomb paintings from that era, especially in the area of present-day Luxor’s west bank, depict craftspeople using the instrument to drill beads and wooden objects.

The team also conducted chemical analysis using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF), which revealed that the object was made from an unusual copper alloy containing arsenic and nickel, as well as notable amounts of lead and silver. According to co-author Jiří Kmošek, this composition would have produced a harder metal that was visually distinct from ordinary copper, potentially indicating deliberate production choices and possible connections to networks of material or knowledge exchange in the eastern Mediterranean during the fourth millennium BCE.

The study is part of the EgypToolWear project, funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and highlights the potential of museum collections for new discoveries. A small object, excavated decades ago and briefly described, revealed not only evidence of early metallurgy but also rare organic remains that help clarify how the tool was used.

Reference: “The Earliest Metal Drill of Naqada IID Dating”, Martin Odler and Jiří Kmošek Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant (Vol. 35, 2025)