7,000-year-old stone circles discovered in Saudi Arabia

Archaeologists in Saudi Arabia have made an impressive discovery by excavating eight ancient stone circles which, according to their findings, were used as dwellings. These finds, located in the Harrat ‘Uwayrid lava field, near the city of AlUla, shed light on the life and practices of communities that inhabited the region approximately 7,000 years ago.

The stone circles, with diameters ranging from 4 to 8 meters, have an intriguing central feature: at least one stone placed in the center of each structure. The excavations revealed that these circles contained the remains of stone walls and entrances, suggesting that they were used as dwellings. The research team theorized that the roofs of these structures could have been made of stone or organic materials, adapting to the environment available at the time.

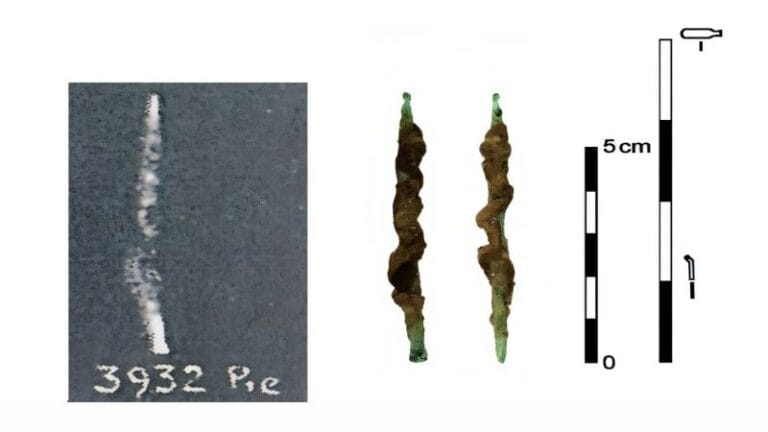

Basalt Tools and Evidence of Subsistence

During the excavations, the archaeologists discovered a significant quantity of stone tools made from basalt. In the five circles investigated, almost 225 kilos of stone tools and debris were found, evidencing a society that relied heavily on the use of stone tools for various activities. In addition, bone remains of sheep, goats and cows were found, indicating the domestication and management of animals as an integral part of this community’s subsistence.

Another fascinating find was the presence of marine shells from the Red Sea, located approximately 120 kilometers west of AlUla. The research team interpreted this discovery as indicative of trade and exchange networks that coexisted with the mobility of these ancient communities. “The presence of these shells suggests the development of trade and exchange networks simultaneous with mobility,” wrote the team.

Comparisons with similar structures in Jordan

The artifacts found in the circles, together with the similarity of these structures to ancient dwellings excavated in Jordan, suggest that many of these stone circles also served as residences. Jane McMahon, honorary research fellow at the University of Western Australia and lead author of the study published in the journal Levant, pointed out that early domestic architecture was predominantly circular, with rectangular houses only appearing at the end of the Neolithic. “Globally, early domestic architecture was always round, and rectangular houses only appear at the end of the Neolithic,” said McMahon.

A Very Different Environment

7,000 years ago, northern Saudi Arabia was significantly wetter than today, although agriculture was not yet practiced. McMahon explained that there is no evidence of cultivation of domesticated plants such as wheat and barley, but it is likely that wild plants were collected and the landscape was manipulated to increase the availability of these species. “There is no evidence of cultivation of domesticated plant species such as wheat and barley, but wild plants were probably collected and perhaps the landscape was manipulated to increase the likelihood and yield of wild species,” said McMahon.

During this period, another stone structure, known as a mustatil (which means rectangle in Arabic), was also built. Excavations at the mustatiles suggest that they had a ritual purpose, possibly including the slaughter of cattle. The coexistence of mustatiles and standing stone circles indicates that these two types of megalithic structures were part of a single cultural entity. The contemporary use of mustatiles and standing stone circles indicates that “these two types of megalithic structures are probably aspects of a single cultural entity,” wrote the team.

Migrations and Cultural Connections

Gary Rollefson, professor emeritus of anthropology at Whitman College and San Diego State University, who did not take part in the research but has carried out extensive archaeological work in the region, believes that the people who built the stone circles were descendants of communities that lived in Jordan and Syria around 500 years earlier. Rollefson noted that the architecture of the stone circles in Saudi Arabia is similar to that found in Jordan, where people also raised sheep, goats and cattle.

According to Rollefson, the migration of these communities may have been driven by population increases resulting from new hunting technologies, such as the “kite” – a series of stone walls used to direct wild animals to hunting grounds. These advances significantly increased the food supply, leading to a population growth that eventually led these communities to migrate south to the region we know today as Saudi Arabia. “They were building up a large population in eastern Jordan and parts of Syria, and they needed to find new hunting grounds, which would have gradually led them south to Saudi Arabia,” he says.

The study was published in the journal Levant.