Symbols in ancient Assyrian temples finally deciphered

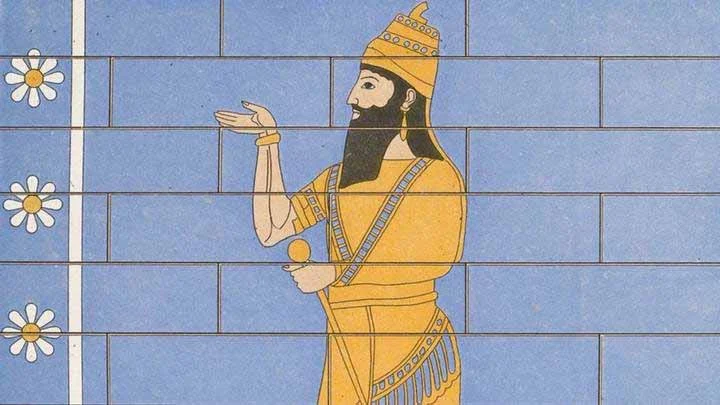

For over a century, archaeologists and scholars have puzzled over a strange sequence of symbols found adorning several ancient Assyrian temples. The five symbols – a lion, eagle, bull, fig tree, and plow – were first discovered through 19th century French excavations at the archaeological site of Khorsabad in modern-day Iraq. This was once the capital city of Dūr-Šarrukīn, established by the mighty ruler Sargon II during the height of the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BCE.

While theories emerged proposing the symbols represented concepts like imperial power akin to Egyptian hieroglyphs, their true meaning remained an enigma. That is, until Dr. Martin Worthington, an expert on ancient Mesopotamian languages at Trinity College Dublin, recently cracked the code. His solution, published in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, reveals the symbols are not abstract icons but rather encode Sargon’s royal name itself.

According to Worthington’s analysis, the Assyrian words for each of the five symbols contain sound components that, when strung together in sequence, phonetically spell out “Sargon” in the ancient language. For instance, the word for “lion” is ūru, contributing the “ū” and “r” sounds, while the term for “fig tree” is tittu, lending the “t” consonants. Piecing together the letters from all five words produces the sounds that form Sargon’s name.

Bolstering this interpretation, Worthington notes some sites utilize only three symbols – lion, tree, and plow – which follow the same linguistic logic to again encode “Sargon.” His theory elegantly explains both the fivefold and trimmed-down versions of the mysterious pictographic code.

“The study of ancient languages and cultures is full of puzzles of all shapes and sizes, but it is not often in the Ancient Near East that one is confronted with mysterious symbols on a temple wall,” commented the researcher.

But the layers of meaning go even deeper. The researcher proposes each symbol simultaneously represented a constellation, cementing Sargon’s legacy in the heavens for eternity while linking him to important Mesopotamian deities. “The effect of the symbols was to assert that Sargon’s name was written in the heavens, for all eternity, and also to associate him with the gods Anu and Enlil, to whom the constellations in question were linked,” Worthington explained.

With this multi-layered symbolic code, the temples ingeniously wove together writing, astronomy, and theology to glorify one of the Assyrian Empire’s greatest rulers. While proving any ancient linguistic theory is inherently challenging given the span of millennia, Worthington argues the cohesiveness of his solution across multiple symbolic variations makes it highly compelling.

“I can’t prove my theory, but the fact that it works for both the five-symbol sequence and the three-symbol sequence, and that the symbols can also be understood as culturally appropriate constellations, seems very suggestive to me,” he stated. “The odds against it all being a fluke are, pardon the pun, astronomical.”

The unveiling of this encrypted ancient code highlights the ingenious advances of societies like the Assyrians, who called Mesopotamia the “cradle of civilization” home over three millennia ago. This was a region where the earliest cities flourished, empires rose and fell, and pivotal developments like the invention of writing around 3400 BCE laid the foundations for much of human culture and technology still influencing the world today.

From the artifacts and cuneiform scripts they left behind, scholars like Worthington continue unraveling new insights into these pioneering civilizations’ achievements, belief systems, and the lives of legendary figures who ruled them.

As he concludes, “This region of the world is often referred to as the ‘cradle of civilization.’ It is where cities and empires were born, and its history is a large part of human history. It is thanks to the Mesopotamian habit of counting in sixties that today we have 60 minutes in an hour, and Abraham (a central figure in three of the world’s major religions) is said to have come from the Mesopotamian city of Ur.”