Lunisolar calendar at Göbekli Tepe may be the oldest in the world

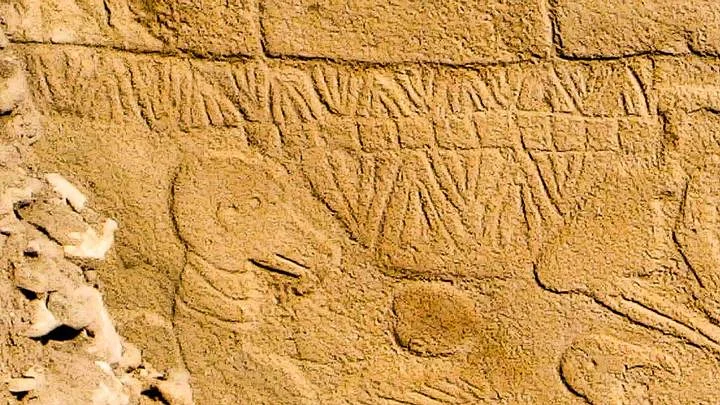

Researchers have discovered what might be the world’s oldest sun and moon calendar at Göbekli Tepe, a 12,000-year-old archaeological site in southern Turkey. The ancient complex, consisting of temple-like enclosures adorned with intricately carved symbols, may hold records of an astronomical event that triggered a significant change in human civilization.

A study published in the journal Time and Mind suggests that the site’s inhabitants created an astronomical calendar to track time and mark changing seasons. The researchers analyzed V-shaped symbols carved on the site’s pillars, interpreting each V as representing a single day. This allowed them to identify a 365-day solar calendar on one pillar, composed of 12 lunar months plus 11 additional days.

The summer solstice appears to be marked as a special day, represented by a V worn around the neck of a bird-like beast thought to depict the summer solstice constellation of that time. Other nearby statues, possibly representing deities, also feature similar V markings on their necks.

The inscriptions at Göbekli Tepe could constitute the world’s oldest lunisolar calendar, based on both lunar and solar cycles, predating other known calendars of this type by millennia. Researchers propose that these inscriptions may have been created to record the date of a comet fragment shower that impacted Earth nearly 13,000 years ago, around 10,850 B.C.

This cosmic event is believed to have triggered a mini ice age lasting over 1,200 years, leading to the extinction of many large animal species. It may have also prompted changes in lifestyle and agriculture, potentially linked to the birth of civilization in the fertile West Asian Crescent.

Another pillar at the site appears to represent the Taurids meteor stream, believed to be the source of the comet fragments. This stream lasted 27 days, emanating from the directions of Aquarius and Pisces. The discovery also suggests that ancient people could record dates using precession, the wobble in Earth’s axis affecting the movement of constellations, at least 10,000 years before Hipparchus documented this phenomenon in ancient Greece in 150 BC.

The inscriptions seem to have retained their significance for the people of Göbekli Tepe for millennia, indicating that the impact event may have sparked a new cult or religion influencing the development of civilization. This finding also supports the theory that Earth faces increased comet impacts as its orbit crosses the path of surrounding comet fragments, which we typically experience as meteor streams.

Dr. Martin Sweatman of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering, who led the research, commented: “It seems that the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were meticulous observers of the sky, which is understandable given that their world had been devastated by a comet impact.” He added, “This event could have sparked civilization by initiating a new religion and motivating developments in agriculture to cope with the cold climate. Possibly, their attempts to record what they saw are the first steps toward the development of writing millennia later.”