Discovery in Australia foreshadows the origin of reptiles

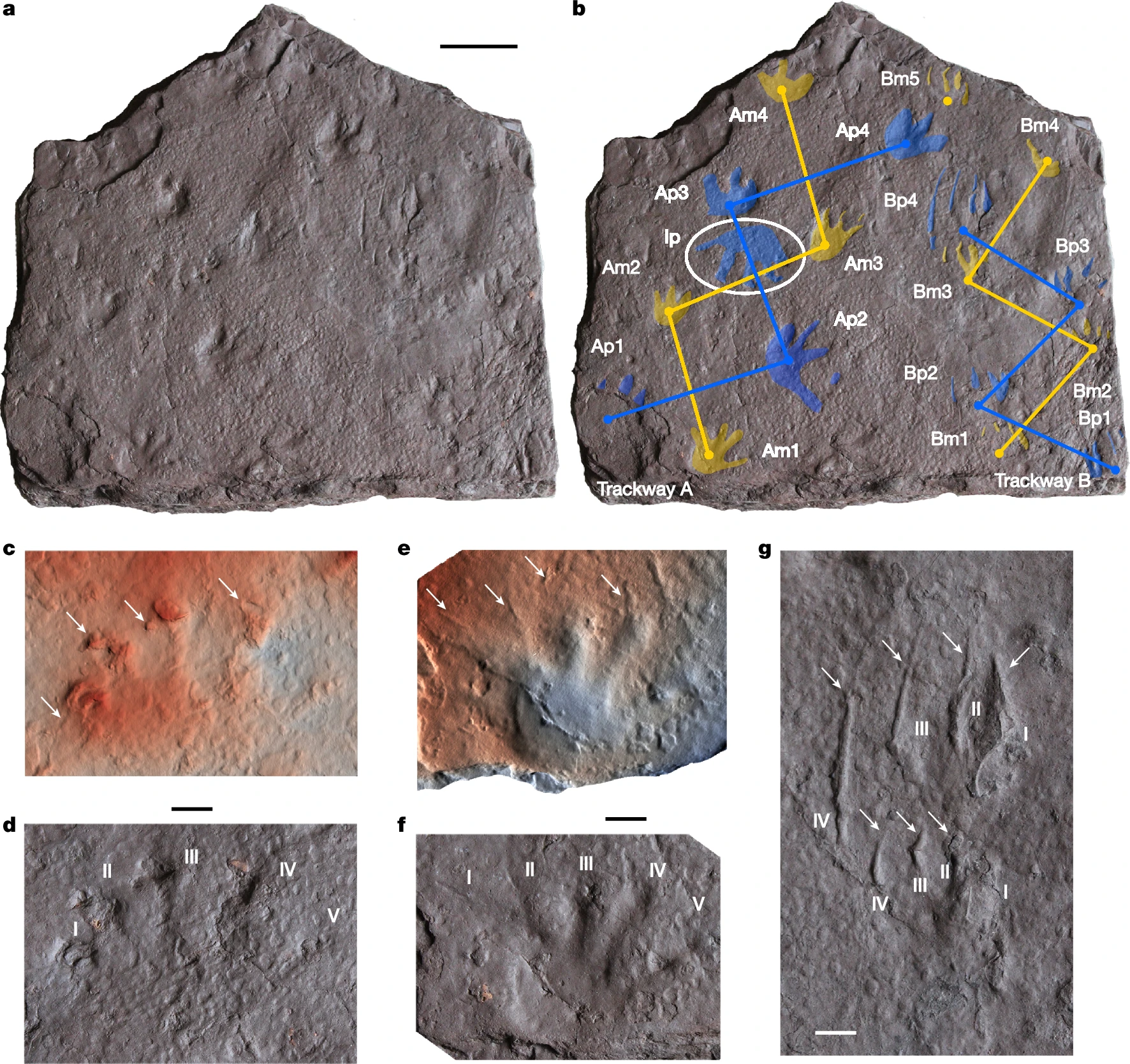

A set of fossilized footprints found on the banks of the Broken River in the state of Victoria, Australia, is changing the history of the evolution of terrestrial vertebrates. According to a study published in the journal Nature, the claw marks recorded in sandstone blocks indicate that amniotes – a group that includes reptiles, birds and mammals – already existed around 355 million years ago, 35 million years earlier than previously believed.

The footprints were discovered by two co-authors of the study, who are not professional scientists, in an area known as Berrepit by the Taungurung, the traditional indigenous people of the region.

The fossilized tracks stand out for having clear impressions of claws, which points to animals closer to reptiles than amphibians. “Having these curved claws in the tracks indicates that they were definitely reptile-like animals,” says paleontologist John Long, from Flinders University.

The footprints don’t show belly or tail drags, suggesting that the animals walked with their bodies upright, a skill considered advanced for the time.

Despite the enthusiasm, there is disagreement about the behavior of the animals that left the tracks. “This discovery is exciting and, if the tracks have been interpreted correctly, the findings have important implications for our understanding of tetrapod evolution,” says Steven Salisbury, a paleontologist at the University of Queensland.

However, he questions whether the animals were actually walking on dry land. “It seems more likely that the tracks were made by an animal that was propelling itself in shallow water, rather than walking on dry land,” he ponders.

Based on the dating of the rocks where the footprints were found and comparative DNA analysis, the researchers suggest that the split between amniotes and amphibians may have occurred around 380 million years ago, in the Devonian period – much earlier than previously estimated.

The study combined radiometric dating techniques, using radioactive decay in volcanic layers, with molecular phylogeny, which compares the genes of current species to estimate the time of evolutionary divergence.

Before this discovery, the oldest fossils of amniotes came from North America, which led us to believe that the group originated in the northern hemisphere. Now, the hypothesis of an origin in the southern hemisphere – more precisely on the supercontinent Gondwana, of which Australia was a part – is gaining strength.

But John Long himself warns: “More fossil evidence is needed to confirm that the south was indeed the place of origin. Australia is a vast area, with few paleontologists working in the field. We still have many unexplored fossil sites where discoveries like this keep coming up.”

This new evidence changes the timeline of terrestrial vertebrate evolution and may indicate that amniotes adapted to the terrestrial environment much earlier than previously thought. It also reinforces the importance of Australia as a frontier that has yet to be explored in the field of paleontology.