Discoveries Reveal Ritual Burials in Prehistoric Mine

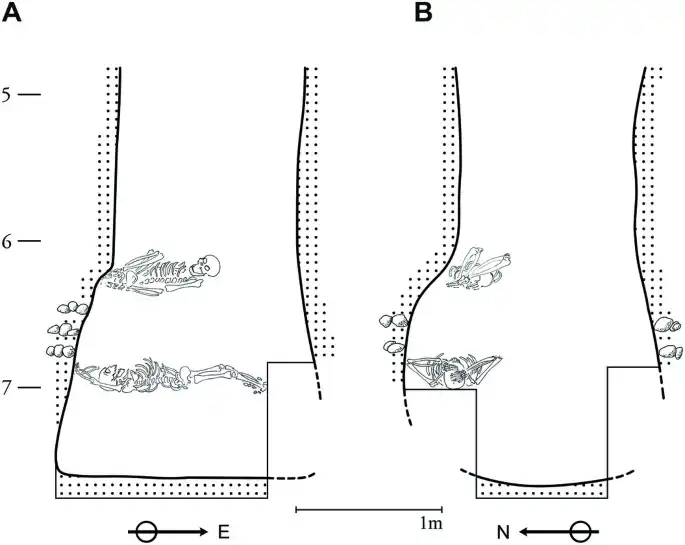

In the heart of the Krumlov Forest, in the southern region of Czechia, archaeologists have made one of the most intriguing discoveries in European prehistory. During excavations of an ancient flint mining pit, the remains of two women and a newborn were uncovered, carefully placed about six meters deep.

The mine, active from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age, was already recognized as one of the largest flint extraction sites in Europe. However, this discovery, dated between 4300 and 4050 BC, raises a compelling question: what led these individuals to be buried inside a mining pit?

The skeletons were arranged on two levels within the shaft. The woman on the upper level showed clear signs of a life of hard labor, with deformed vertebrae, bone injuries, and muscle wear uncommon for someone of her physical stature.

Just below, the body of the second woman was found. Resting on her chest was the skull of a newborn, with the tiny bones scattered around the pelvic area, suggesting that the child was intentionally placed there at the time of burial.

Alongside the bodies were also the remains of a dog — an element often associated with symbolic or ritual practices in the context of Neolithic Europe.

Detailed analyses revealed that both women were between 30 and 40 years old and shared a direct familial bond — likely sisters. They were small by the standards of the time, measuring approximately 148 cm and 146 cm, but showed physical markers indicating well-developed musculature and physical strain, especially in the legs, hips, and spine.

Osteological evidence also reveals a childhood marked by severe hardship. The so-called Harris lines on their bones — scars from growth disruptions caused by hunger or disease — and defects in dental enamel stand as testimony to the struggles they faced from an early age.

Interestingly, in adulthood, their diet was rich in protein, including meat in higher proportions than was typical for Neolithic communities in the region. This may be directly related to the physical demands of working in the mines.

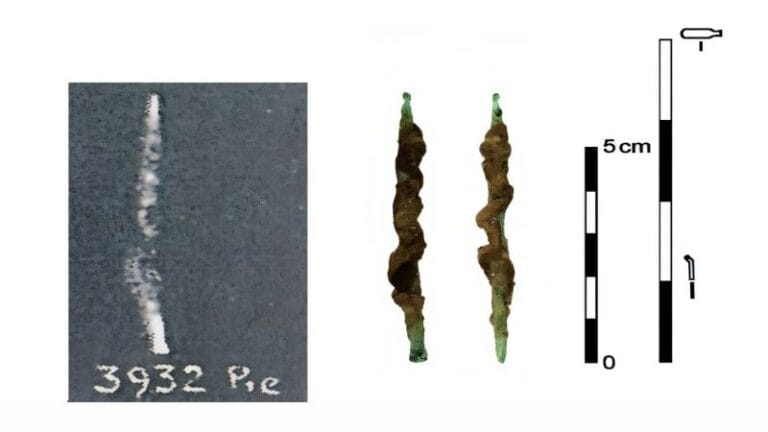

The signs of physical wear are striking. One of the women suffered a forearm fracture that never healed properly, resulting in a pseudoarthrosis. This indicates that, even injured, she continued working.

Both exhibited serious spinal deformities, such as fossilized hernias (Schmorl’s nodes), spondylolysis (fractures in the vertebral arches), and bone hypertrophy at muscle attachment sites—evidence of repetitive and prolonged strain.

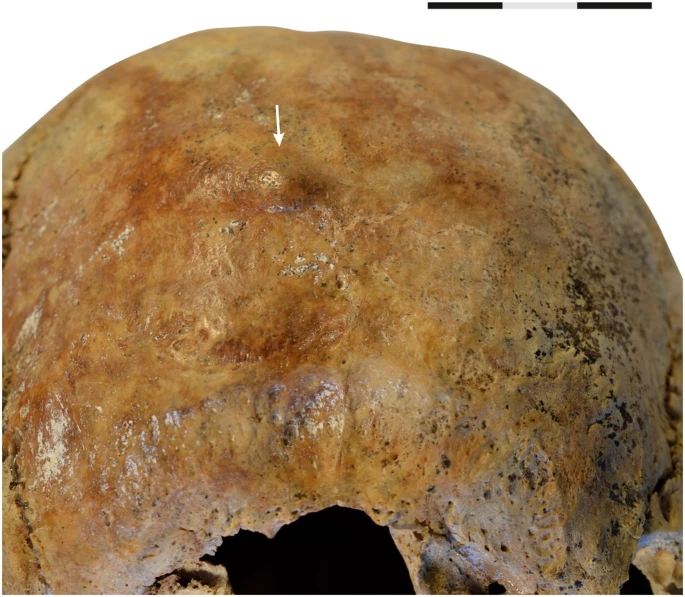

Additionally, one of them had a small benign bone tumor on her skull, and both suffered from periodontal problems. Abnormalities in the ear, known as tympanic dehiscences, were also found. Although these did not affect their hearing, they reinforce the pattern of shared anatomical traits between the two—further confirming their kinship.

The positioning of the bodies, the presence of the newborn—who, according to genetic analyses, was not the child of either woman—and the remains of the dog strongly suggest a ritual burial.

One hypothesis is that these bodies were thrown or placed in the pit as part of a ritual marking the closure of mining activity, a practice documented in other prehistoric cultures.

Another, more unsettling possibility suggests that these women may have been victims of human sacrifice, related to spiritual beliefs about the underground and ancestry.

The mine environment itself, with its numerous open and abandoned shafts, seems to have transformed over the centuries into a sacred landscape, where the living and the dead shared the same symbolic space.

Far beyond the discovery of the bones, the study allowed science to give a face to these women who lived over six thousand years ago. Using 3D scans of the skulls, combined with genetic analysis — which identified traits such as eye color — and anthropometric parameters, the researchers reconstructed their features with impressive realism.

The results reveal distinct features: one of the women had green or light brown eyes, likely accompanied by dark hair. The other had blue eyes and possibly lighter hair — a genetic diversity already present in Neolithic populations of Central Europe.

📚 Reference: Vaníčková, E., Vymazalová, K., Vargová, L., Tvrdý, Z., Oliva, M., Brzobohatá, K., Fialová, D., Skoupý, R., Krzyžánek, V., Nývltová Fišáková, M., & Drozdová, E. (2025). Ritual Burials in a Prehistoric Mining Shaft in the Krumlov Forest (Czechia). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 17, Article 146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02251-1