Ancient Egyptian tombs may have stored radioactive waste

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science suggests that ancient Egyptian tombs could have served as repositories for nuclear waste, potentially triggering illnesses and even deaths attributed to curses.

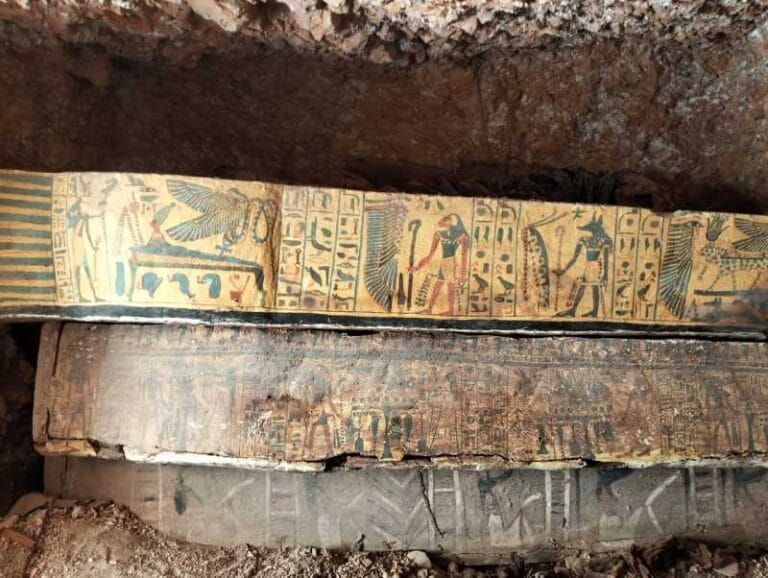

This study reveals a surprising connection between the literature of ancient Egypt and the principles of modern nuclear technology. By analyzing texts dating back to around 2300-2100 BC, including the renowned Pyramid Texts and the Sarcophagus Texts, researchers have identified references to processes and substances that notably evoke uranium-based materials. This suggests a level of technological sophistication hitherto underestimated in ancient Egyptian civilization.

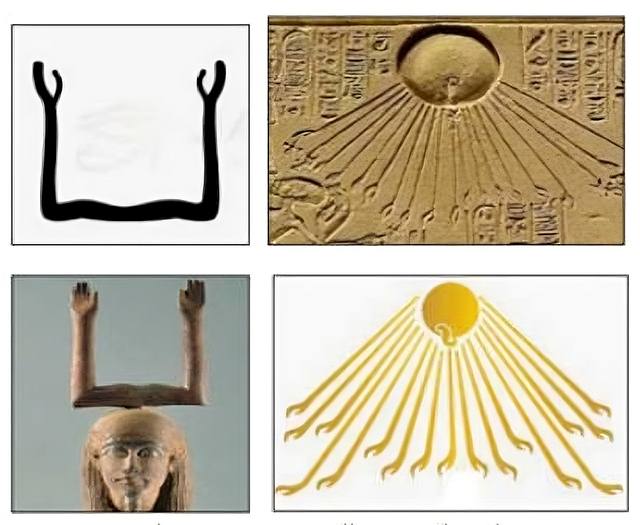

For example, Osiris, a central figure in Egyptian mythology, is described as being “transformed into light,” which suggests the possibility of the release of nuclear energy, implying a primitive understanding of the conversion of matter to energy. Other descriptions of Osiris as a “primordial substance,” “formless matter,” and “light in his birth,” along with the mention that he is “formed of atoms,” indicate an incipient conception of atomic theory or the fundamental properties of matter.

References to invisible and mystical emissions of “saffron cake” effluvia, possibly related to a “yellow cake” (uranium oxide), suggest a symbolic association with uranium, a crucial element in the context of nuclear energy. These discoveries point to a possible ancient and mystical understanding of nuclear components, which challenges traditional conceptions about the extent of scientific knowledge in ancient Egyptian civilization.

“This connection between a mystical substance and a radioactive material could imply an early knowledge or use of radioactive elements, which has not been recognized to date,” says Ross Fellowes, author of the study.

According to the study, “a sequence of features suggests that unnatural radiation in the mastaba tombs is consistent with the storage of nuclear waste.”

“The symbolism found on stone vessels, labeled with animals representing different types of radiation, reflects an awareness of the types of radiation and their associated dangers,” Fellowes writes.

The textual references to the preparation of “magic foods” through techniques such as diffusion, purification tents and centrifuges also denote a refined mastery of material purification processes. “Here, a reexamination of standard translations reveals frequent and clear descriptions of nuclear technology,” says the researcher.

The study challenges previous interpretations of the “Pharaoh’s curse” and points to the presence of unnatural radiation sources at relevant historical sites. Previous research has identified dangerous levels of radiation, especially radon gas, in ancient Egyptian tombs. However, the new research goes further, establishing a correlation between these high levels of radiation and unusual cases of mortality among Egyptologists, as well as suggesting a possible link with uranium-based technologies.

“Data from early modern field Egyptologists and their associates exposed to tomb excavation reveal high rates of cancer deaths, nominal cardiovascular failure, and other symptoms typical of hematopoietic cancer, corresponding to what is now recognized as radiation sickness,” says Fellowes .

The author evidently refers to the most famous Egyptian curse of all: that associated with Tutankhamun.

“The nature of the curse was explicitly inscribed on some tombs, one of which was presciently translated as: ‘those who break this tomb will find death from a disease that no doctor can diagnose’ (Hawass, 2000, pp. 94- 97). The ancient curse has been recognized by modern archaeologists,” he argues.

“British Egyptologist Arthur Weigall, Howard Carter’s rival in excavations at Thebes, watched an exultant Carnarvon (along with Carter) enter Tutankhamun’s tomb and commented to a colleague: ‘he will be dead in six weeks’ (Nelson, 2002, pp . 1482-1484). Ironically, Carnarvon died a few weeks after an uncertain diagnosis of blood poisoning and pneumonia, while Weigall died prematurely at age 54 from cancer and Carter died later, at age 65, from Hodgkin’s lymphoma.”

The full study , which will certainly provoke a lot of controversy among the most orthodox Egyptologists, can be seen below: