Chimpanzees are capable of speech?

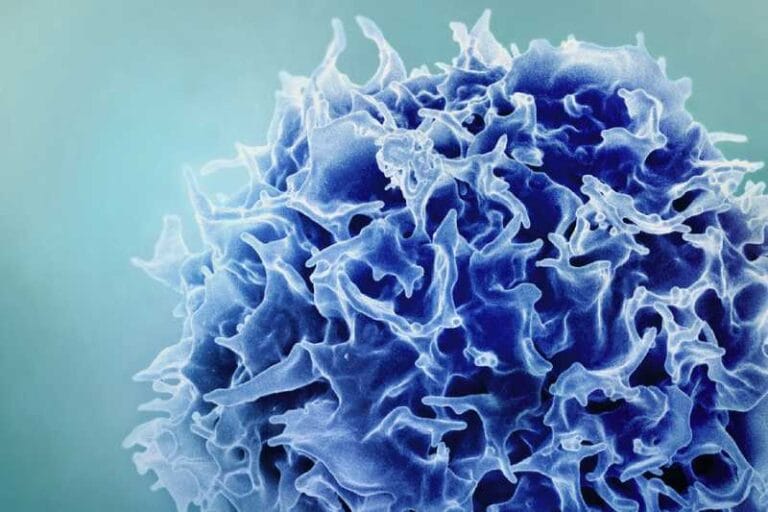

For decades, the scientific community has held firm to the belief that humans are the sole primates capable of speech. This long-standing assumption has recently been challenged by a groundbreaking study published in Nature: Scientific Reports, shedding new light on the vocal abilities of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom – chimpanzees.

The research, led by Axel G. Ekström and colleagues, centered around the analysis of footage featuring two chimpanzees, Renata and Johnny, who were recorded uttering the word “mama.” These instances, though separated by decades, provide compelling evidence that chimpanzees possess the neural circuitry necessary for rudimentary speech production.

Renata’s story dates back to 1962 when she was featured in a Universal Newsreel segment titled “Now Hear This! Italians Unveil Talking Chimp.” The footage, largely forgotten until now, captured a moment that defied conventional wisdom about primate capabilities. As described in the newsreel:

“As explained by her foster mother, this is one of the most extraordinary chimps in the world. You don’t have to know Italian to understand Renata’s accent when she gets her cue.”

Similarly, Johnny, another chimpanzee, was recorded in 2007 saying “mama” in response to his owner’s prompts. These recordings, when subjected to rigorous phonetic analysis, revealed that chimpanzees are indeed capable of producing syllabic utterances, specifically the consonant-vowel combination required for the word “mama.”

The study’s findings challenge our understanding of primate vocal abilities. The researchers state:

“We recovered original footage of two enculturated chimpanzees uttering the word ‘mama’ and subjected recordings to phonetic analysis. Our analyses demonstrate that chimpanzees are capable of syllabic production, achieving consonant-to-vowel phonetic contrasts via the simultaneous recruitment and coupling of voice, jaw and lips.”

To further validate their observations, the team conducted an experiment where human participants were asked to listen to the chimpanzee utterances without knowing their source. Remarkably, the listeners consistently perceived these vocalizations as syllabic utterances, primarily identifying them as “ma-ma.”

It’s important to note that while these findings are significant, they don’t suggest that chimpanzees naturally use speech in the wild. Both Renata and Johnny learned their vocal skills through human coaching, highlighting the role of enculturation in developing these abilities. Nevertheless, the study concludes that “Chimpanzees possess the neural building blocks necessary for speech,” even if they don’t typically use this capacity in their natural environment.

This research not only expands our understanding of chimpanzee capabilities but also offers intriguing insights into the evolution of human language. The word “mama” holds particular significance in this context. As the study’s authors point out:

“Accordingly, it has been argued that ‘mama’ may have been among the first words to appear in human speech. Our data complements this picture: chimpanzees can produce the putative ‘first words’ of spoken languages.”

While speech may not be a natural form of communication for chimpanzees, they do possess sophisticated communication systems. Recent studies have shown that chimpanzees use a complex array of gestures to convey messages, much like humans do. Moreover, some chimpanzees, like the bonobo Kanzi, have demonstrated an impressive ability to understand human language, with a reported vocabulary of nearly 3,000 words.

The implications of this study extend beyond just chimpanzees. By demonstrating that our closest evolutionary relatives possess the basic neural architecture for speech, we gain valuable insights into the origins and development of human language. It raises intriguing questions about the evolutionary path that led to our unique ability for complex verbal communication.

As we continue to explore the cognitive and communicative abilities of great apes, we may need to reassess our assumptions about the uniqueness of human language. While the gap between human speech and chimpanzee vocalizations remains vast, this study suggests that the foundations for spoken language may be more deeply rooted in our evolutionary history than previously thought.

The study was published in Nature: Scientific Reports.