Cow-Free Milk Proteins

A study published in the journal Trends in Biotechnology reveals an innovative solution for producing dairy proteins without the need for cows. European researchers have successfully manufactured functional casein using bacteria, an alternative that could reduce the environmental impacts of livestock farming and boost the sustainable dairy market.

Casein is the main protein in milk, essential for making cheese, yogurt, and other dairy products. It is responsible for important properties such as texture, creaminess, and the ability to transport nutrients, especially calcium. The challenge of producing this protein outside of animals has always been replicating a specific chemical modification: phosphorylation.

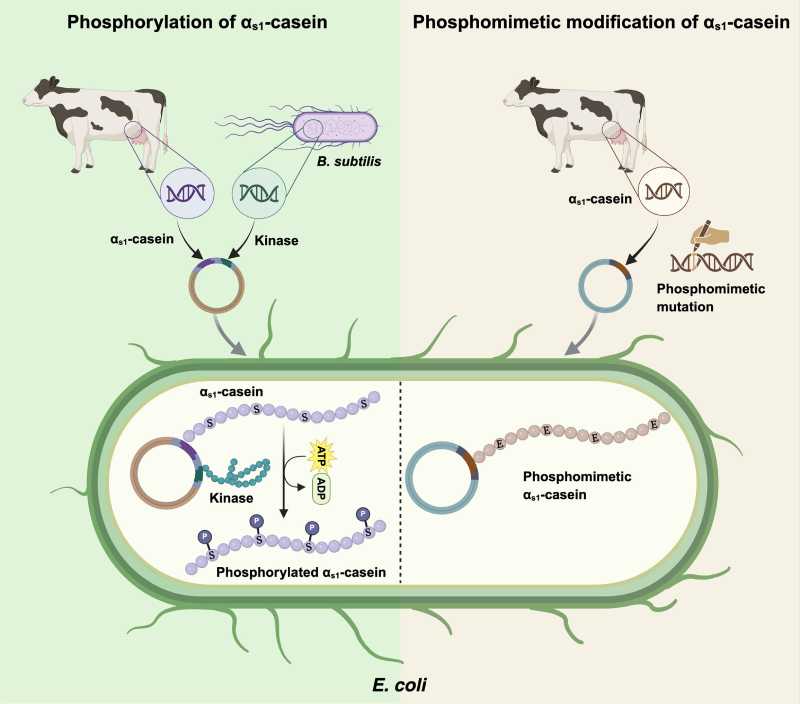

Phosphorylation is a natural process that occurs in mammals, where phosphate groups are added to casein. This detail is crucial for the protein to bind to calcium and form micelles—tiny structures responsible for the stability and functionality of milk.

Bacteria such as Escherichia coli, widely used in biotechnology, do not perform this modification on their own, which has limited previous attempts to produce functional casein.

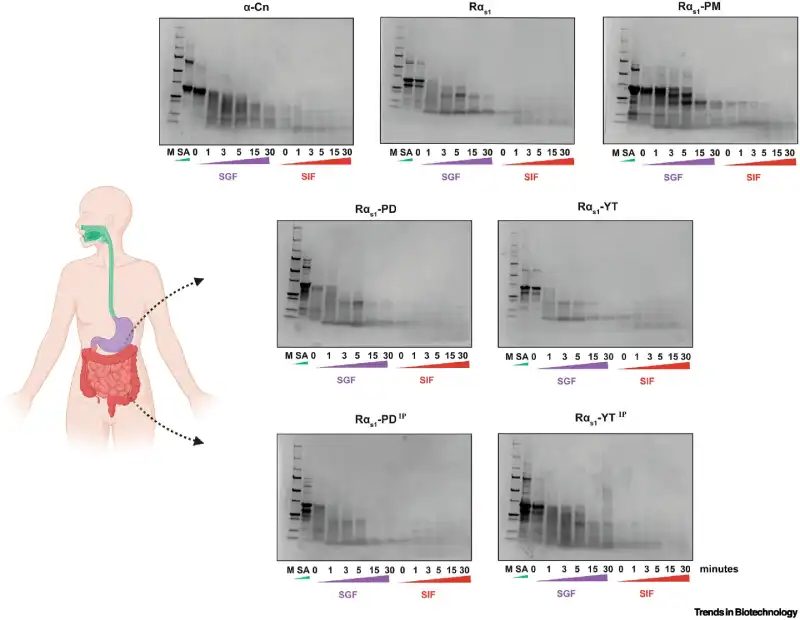

The researchers also tested how the lab-produced proteins behave during digestion. The results showed that, just like conventional milk proteins, the lab-grown versions were rapidly digested in simulations of the gastrointestinal system. Below, you can see how the proteins behaved throughout the digestion process:

To address the challenge, the research team relied on two different strategies. The first was to genetically modify E. coli bacteria to produce enzymes called kinases, derived from another bacterium, Bacillus subtilis. These enzymes are capable of phosphorylating casein during its production inside the bacterial cells.

The second approach eliminated the need for enzymes: the scientists directly altered the structure of the casein by substituting certain amino acids with others that mimic the electrical charge of phosphorylation, a technique known as phosphomimetic modification.

Tests showed that both approaches worked well. The phosphorylated and phosphomimetic versions of casein efficiently bound to calcium and maintained properties similar to those of bovine milk proteins. This means they could be used in the food industry to produce products with taste and texture comparable to traditional dairy.

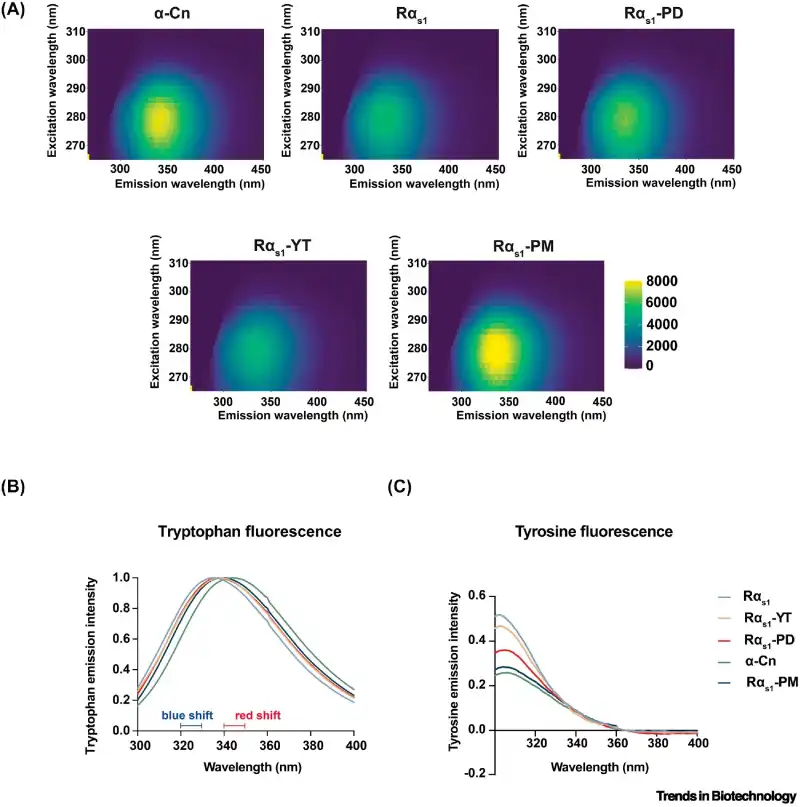

In addition to calcium-binding capacity, the study also analyzed the structural characteristics of the produced casein. Using fluorescence methods, the researchers observed that the structure of the recombinant proteins closely resembled that of bovine casein, maintaining the functional integrity required for food applications.

Livestock farming is often cited as one of the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions and excessive water consumption. Microbial production of dairy proteins emerges as an alternative to reduce these environmental impacts, while also offering new options for people with lactose intolerance or allergies to conventional milk.

Although the method is still in the laboratory stage, the study points to a future where cheese and yogurt could be produced without cows and with a lower environmental impact—without compromising the nutritional quality of dairy products.