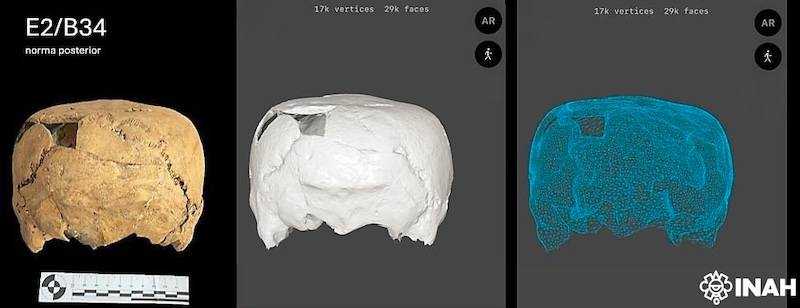

Unusual 1,400-year-old cube-shaped skull discovered in Tamaulipas.

An unprecedented discovery has surprised researchers from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) in the state of Tamaulipas. During a recent review of bone materials at the Balcón de Montezuma archaeological site, the skull of a middle-aged man was identified with a cranial modification never before seen in the area: a cube-shaped head.

The discovery, dating back approximately 1,400 years, provides the first evidence that the inhabitants of this region in northeastern Mexico practiced this specific style of cranial modeling.

The archaeological site, located in the Sierra Madre Oriental, was inhabited by various ethnic groups between 650 B.C. and A.D. 1200. Around A.D. 400, the settlement flourished as a village made up of about 90 circular houses distributed across two plazas.

It was in this context that the individual was found. According to INAH physical anthropologist Jesús Ernesto Velasco González, who explained the finding in a recent statement, the shape of the skull is ‘unprecedented’ in the local record.

Although artificial cranial modification was a common practice throughout Mesoamerica, the styles varied greatly.

- Oblique tabular modification: This is the most popularly known style, in which infants’ heads were wrapped to produce a conical or elongated shape (sometimes colloquially described as having an ‘alien-like’ appearance).

- Erect tabular modification: Common at Balcón de Montezuma, where boards were used to flatten the forehead and the back of the head, resulting in a taller or more pointed skull.

However, the newly discovered skull shows a distinct variant of the erect modification. The top of the head was intentionally flattened, creating a square-shaped structure that experts classify as “parallelepipedal” — similar to a cube or rectangular prism.

Since this type of cubic deformation, or ‘planolambdoid erect tabular’ modification, had previously been documented in distant regions such as Veracruz or the Maya area, the archaeologists’ first hypothesis was that the man was a foreigner who had migrated to Tamaulipas.

To confirm this, the team subjected the remains to chemical analyses of the bones and teeth. The results were revealing: the man was not a foreigner. The data indicate that he was born, lived, and died in the Balcón de Montezuma area, deepening the mystery of why he bore a cultural marker typical of other civilizations.

The researchers speculate that this unusual head shape may have held a specific cultural meaning that remains unknown. In pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, cranial shape often served as a marker of ethnic identity or social status.

Although the individual was local, it is possible that the people responsible for shaping his head — a process that begins in early infancy — belonged to a different cultural group or were influenced by external traditions.

Tonantzin Silva Cárdenas, director of the INAH Center in Tamaulipas, stated that research on the recovered materials is ongoing. These studies are key to expanding our understanding of the site and unraveling the complex historical and cultural relationships that existed between the pre-Hispanic groups of the north and the rest of Mesoamerica.