Discovery of 1,300-Year-Old Throne Room of Moche Queen

Archaeologists in Peru have made a significant discovery: a throne room approximately 1,300 years old, adorned with murals depicting a female ruler from the Moche culture, a civilization that flourished on the northern coast of Peru. Although the remains of the ruler have not been found, the team remains hopeful about the future developments of the investigations.

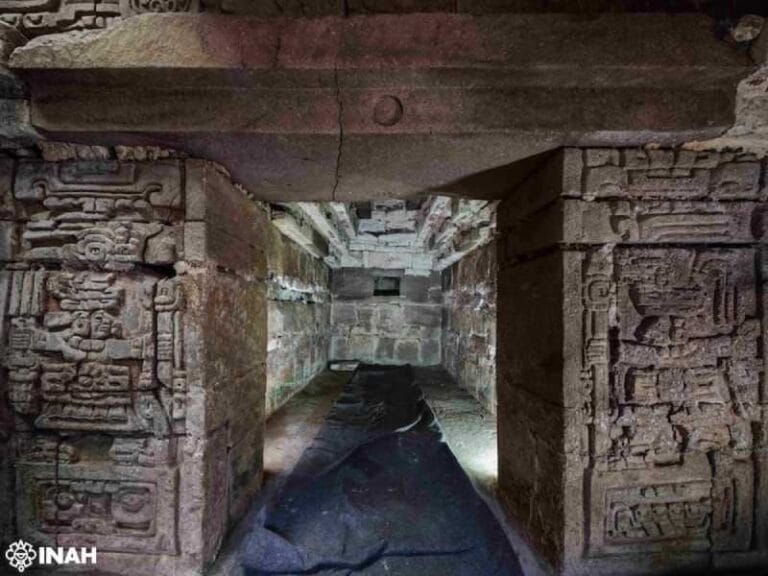

The throne room was identified at the archaeological site of Pañamarca and dates back to the 7th century A.D., a period when the Moche civilization reached the height of its influence. According to the team of archaeologists, the Moche thrived between 350 and 850 A.D., engaging in the construction of architectural complexes, elaborate tombs, and intricate works of art.

An example of this is the pottery depicting human faces, which showcases the level of artistic sophistication and technical skill achieved by this society.

The Moche culture, which developed before the advent of writing in Peru, is notable for making its artistic representations and archaeological findings essential for understanding its social structure and cultural beliefs.

“Although other female rulers from pre-Inca Peru are known, a throne room of a queen had never before been found in Pañamarca or anywhere else in ancient Peru,” the report emphasized.

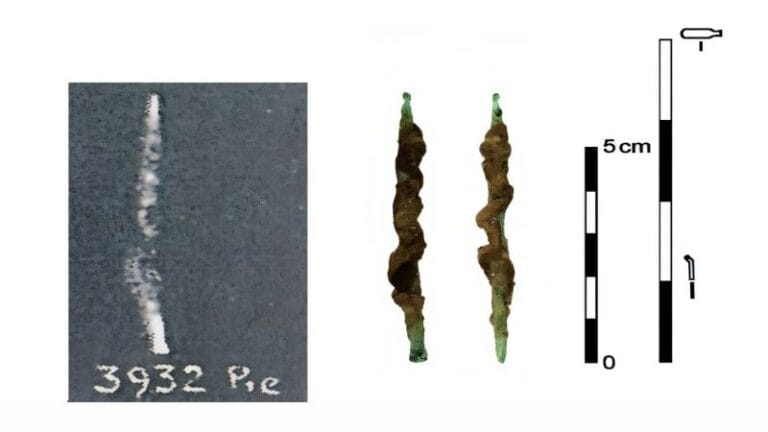

The throne, made of adobe, shows traces of green stone beads and strands of human hair, which, according to the archaeologists, may be associated with the ruler depicted in the murals. To verify this possibility, DNA analyses are planned, which could determine if the material is indeed linked to the female figure portrayed in the mural paintings.

The murals decorate pillars, walls, and the throne itself, depicting the queen in various scenes that illustrate her status and authority. In one representation, she wears a crown and holds a chalice, expressing a posture of prestige and leadership.

In another scene, she wields a scepter while men from her entourage offer her textiles and other tributes, highlighting her role in the redistribution of resources. In a third image, the ruler is seated on her throne, interacting with an enigmatic figure characterized as half-man, half-bird—a possible representation of a symbol of spiritual power or divine intermediary.

“We do not have evidence of a tomb at this time,” explained Michele Koons, director of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science and one of the leaders of the excavation, referring to the fact that the remains of the queen have not yet been found.

“It is unclear what kind of kingdom this female leader ruled over.” According to her, “the political organization of the Moche is a topic of great interest in the studies of this culture. There is evidence that it consisted of independent political units that interacted with one another,” she added, noting that these political units may have shared similar religious ideas and artistic styles.

Women leaders were not uncommon figures in Moche society, nor in subsequent dynasties of northern Peru. Current knowledge about these rulers largely derives from discovered tombs, such as that of the renowned “Señora de Cao,” a mummy from the Moche culture found at Huaca El Brujo in 2006.

This woman, who likely held a position of power, was buried with various prestige items, including jewelry, ornaments, and weapons, such as clubs and atlatls—devices that assist in launching darts and spears over long distances.

The wealth of items in the tomb suggests her high social status and possibly a governmental role.

Koons emphasized that, in some cases, contemporary archaeologists may misinterpret the role of women in high-status burials, highlighting the need for careful contextual analysis of these findings. “Moche tombs of high-ranking men are often described as belonging to ‘lords,’ while those of women are referred to as ‘priestesses,'” she commented. She suggests that some of these “priestesses” may have actually been rulers.

The investigation of the archaeological site of Pañamarca has a history that spans over seven decades, with the first murals being identified in the 1950s. The current research team began its work in 2018, and in August 2022, made a remarkable discovery: two murals depicting two-faced figures in a ceremonial room.

The recent discoveries, including the throne room and its detailed murals, continue to reveal nuances of the complex social, religious, and political structure of the Moche, providing a deeper understanding of this fascinating civilization and its cultural dynamics.