Earliest writing appeared on Mesopotamian trade stamps

A new study suggests that the world’s oldest known writing system was influenced by symbols used in trade — specifically, engravings found on cylinders used to exchange agricultural products and textiles.

The discovery supports an idea proposed in previous research: that cuneiform script — developed in early Mesopotamia around 3100 B.C. and believed to be the earliest writing system — partly originated from methods of accounting to track the production, storage, and transport of goods.

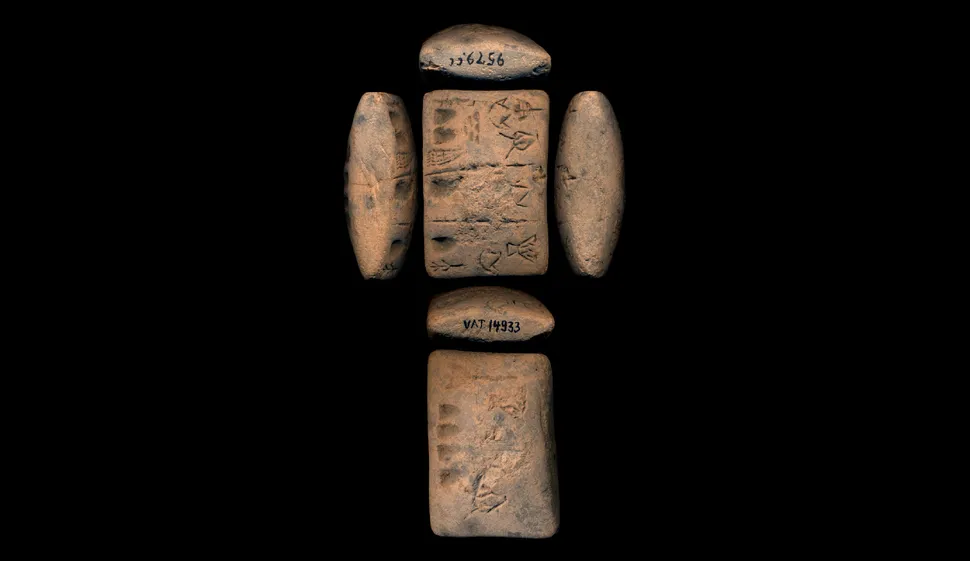

The researchers found that several symbols engraved on stone “cylinder seals” were later adapted into “proto-cuneiform,” an early form of the cuneiform script used in southern Mesopotamia, in what is now southern Iraq. Their findings were published Tuesday (Nov. 5) in the journal Antiquity.

These cylinder seals were used for thousands of years across Mesopotamia, where they were rolled onto clay tablets to imprint their motifs—commonly to authenticate a transaction or, later on, to seal letters.

Some of the seals analyzed in the new study date back to around 4400 B.C., more than a thousand years before the invention of writing. “We focused on seal imagery that originated before the invention of writing, while continuing to develop into the proto-literate period,” study co-authors Kathryn Kelley and Mattia Cartolano, both researchers in the Department of Classical Philology and Italian Studies at the University of Bologna, said in a statement.

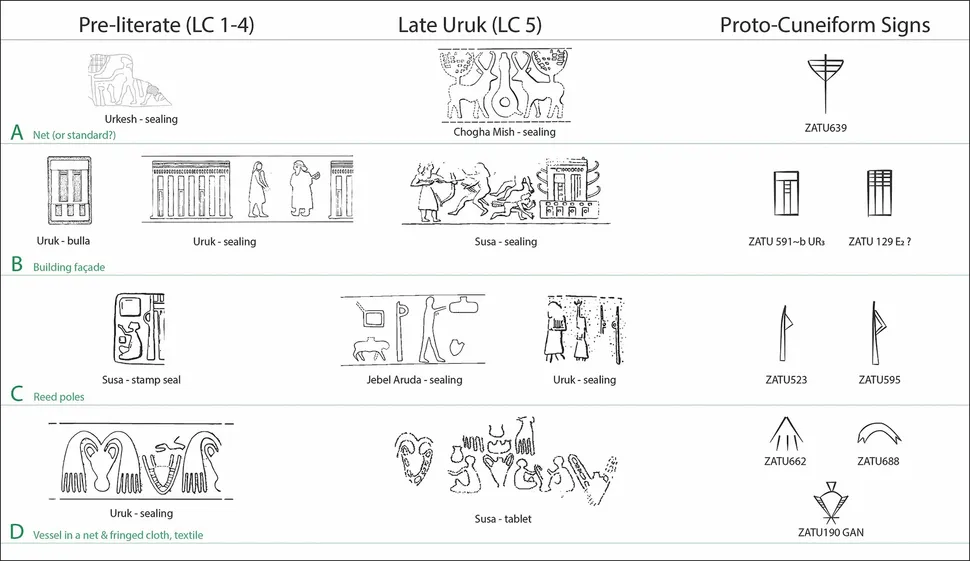

The team identified seal motifs depicting the transport of jars and cloth between various Mesopotamian cities, likely involving temple institutions. The researchers propose that these motifs evolved into proto-cuneiform signs in early records documenting the trade of agricultural goods and textiles.

According to the authors, the discovery—though met with some skepticism—demonstrates a continuity between these “preliterate” seals and early writing forms.

“It proves that the motifs known from cylinder seals are directly related to the development of writing in southern Iraq and shows how meaning was transferred from preliterate motifs into script,” they wrote in the statement.

Cuneiform writing involved using a stylus to press wedge-shaped impressions into unbaked clay, creating symbols that represented sounds and allowed the recording of spoken language. These clay tablets could then be dried or baked, preserving the inscriptions.

This writing system was first developed by the Sumerians, who lived in early cities across southern Mesopotamia from around 5500 to 2300 B.C. It was later adopted by the Akkadian Empire, based in Akkad, who used the Sumerian system to write in their own language. Cuneiform written in Akkadian became the dominant written language of Mesopotamia for over 2,000 years, spanning the Babylonian and Assyrian periods.

The study draws attention to several motifs found on preliterate cylinder seals, which the authors suggest later evolved into proto-cuneiform signs on 5,000-year-old clay tablets from Uruk in southern Mesopotamia. These motifs include symbols representing a building, reed poles, and fringed cloths placed in a container.

The researchers hope their findings will aid scholars in deciphering additional proto-cuneiform symbols and deepen the understanding of seal motifs.

“The conceptual leap from pre-writing symbolism to writing is a significant development in human cognitive technologies,” study co-author Silvia Ferrara, a professor in the Department of Classical Philology and Italian Studies at the University of Bologna, said in the statement. “The invention of writing marks the transition between prehistory and history, and the findings of this study bridge this divide by illustrating how some late prehistoric images were incorporated into one of the earliest invented writing systems.”

Anthropologist Gordon Whittaker, an expert on the origins of cuneiform at the University of Göttingen in Germany who was not involved in the study, called it “interesting and thought-provoking.” But he cautioned that it may be premature to suggest the motifs on cylinder seals were “stimuli for the invention of writing.”

“In the few instances in which the same item appears to be depicted in both a seal and a proto-cuneiform sign, there is no obvious causal relationship that would link the one with the other,” he told Live Science in an email.

“Furthermore, several of the shapes — such as a narrow oblong without internal detail — are simply too general or vague to be helpful to the authors’ argument,” he said.

University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Holly Pittman, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the new research supports her theory from about 30 years ago: that the imagery on seals significantly influenced proto-cuneiform writing.

Pittman noted that her idea had been dismissed at the time but expressed satisfaction that the authors of the new study had arrived at the same conclusion.

As much as I love these cylinder seals I don’t buy into the history. Ancient civilizations been around far longer and so has advances technology. Why are we being fed this timeline?

I see your point, Vincent! It’s fascinating to think about the possibility of ancient civilizations and advanced technologies existing longer ago than the traditional timeline suggests. Archaeology is constantly evolving with new discoveries and methods that challenge our previous ideas about the past. However, the idea of cylindrical seals and the first writing systems in Mesopotamia is based on the concrete evidence we have so far. This system of writing in trade records is one of the earliest forms we know of, but we are certainly still discovering more about the rich and complex human history. Who knows what else we might find that could expand this timeline even further?