Facial heat patterns reveal vital health clues

A quick examination of the face can reveal whether we are ageing well and our risk of developing certain diseases. Chinese scientists have found that comparing the heat coming off the nose, cheeks and eye area could be an “ideal monitoring and screening tool for healthy ageing“.

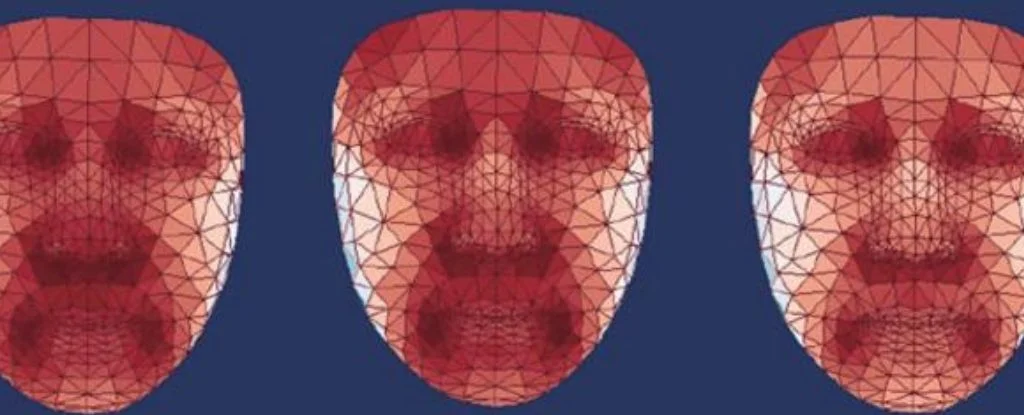

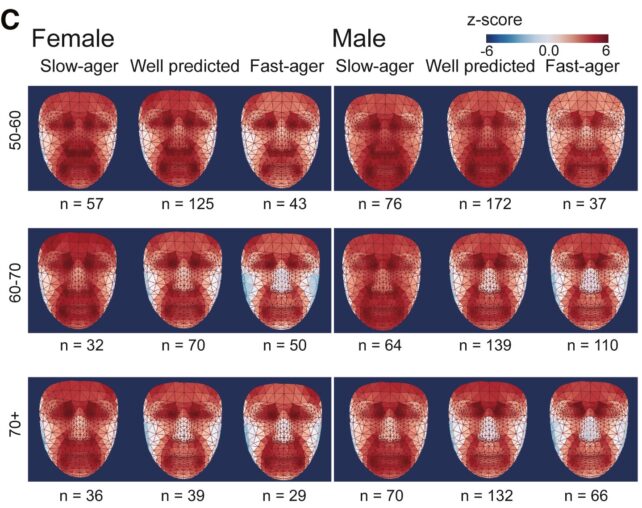

Trained with facial temperature data from 2,811 Chinese participants aged between 21 and 88, an artificial intelligence program identified facial thermal patterns indicative of a person’s “biological clock”. For example, the temperature of the nose decreases with age more quickly than other areas of the face, while the temperature around the eyes tends to increase.

People with warmer noses and colder areas around the eyes may have a slower facial thermal clock. The researchers found that the thermal profile was linked to lifestyle factors and metabolic health. People with diabetes had a facial thermal profile six years older than their healthy peers of the same age.

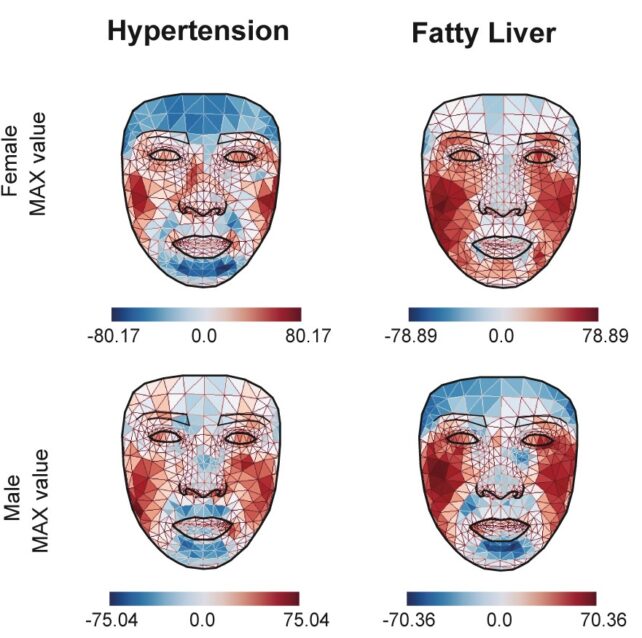

The machine learning model was able to automatically analyze a person’s facial thermal map to predict metabolic disorders, such as fatty liver disease or diabetes, with over 80% accuracy. Individuals with metabolic disorders had higher temperatures in the eye area, while participants with high blood pressure had higher temperatures in the eyes and cheeks. Men with hypertension usually had colder noses.

“The thermal clock is so strongly associated with metabolic diseases that previous facial imaging models have not been able to predict these conditions,” says Jing-Dong Jackie Han from Peking University in China. “We hope to apply thermal facial imaging in clinical settings, as it has significant potential for the diagnosis and early intervention of diseases.”

Biological clocks tick at different rates for everyone, meaning each person ages differently. For years, scientists have sought ways to measure this hidden aspect of health. Apart from some non-invasive methods like scanning the human eyeball, tests measuring the physical signs of biological aging—especially those in the blood—have been challenging to achieve quickly, conveniently, or affordably.

Human faces contain “a wealth of information” that could be easily accessed for this purpose, the researchers argue. While a person’s core body temperature is known to decrease with age, the way facial temperature changes over time remains largely unknown. Studies have often linked high body temperatures to high metabolic rates, and now, the same seems to hold true for facial temperatures.

The current research, however, is limited to samples of data collected from people in China, making it unclear if the results can be generalized to other populations. Facial heat can also be influenced by the environment and emotions, which is why participants were imaged in a temperature-controlled room while in a calm state.

To investigate why thermal facial images change with age, researchers analyzed the bloodwork of 57 healthy individuals from a hospital in China, along with thermal and 3D facial readings of this smaller cohort. They found that increased temperatures around the eyes and cheeks were linked to increased cellular activity associated with inflammation.

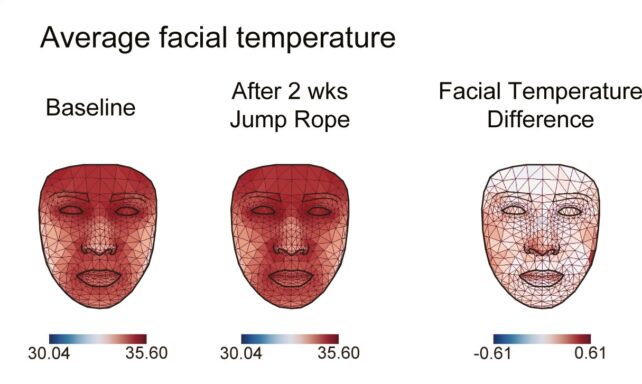

In another part of the study, the researchers asked 23 participants to jump rope daily for two weeks to see if exercise could affect thermal facial ‘age’. By the end of the study, the cohort had reduced their thermal age by an average of five years, while their non-jumping peers showed no significant difference.

More research is needed to confirm and explain these associations, but the results are promising enough that the study’s researchers will continue to explore whether thermal facial imaging can predict healthy aging in other ways too.

The study was published in Cell Metabolism.