Hidden Diabetes Risk Identified by AI

A new study led by researchers at the Scripps Research Translational Institute is challenging the traditional way we diagnose and monitor type 2 diabetes. Published in Nature Medicine, the study reveals that glucose spikes are not exclusive to people with diabetes. Even individuals considered healthy can experience concerning fluctuations that go undetected by standard tests like hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

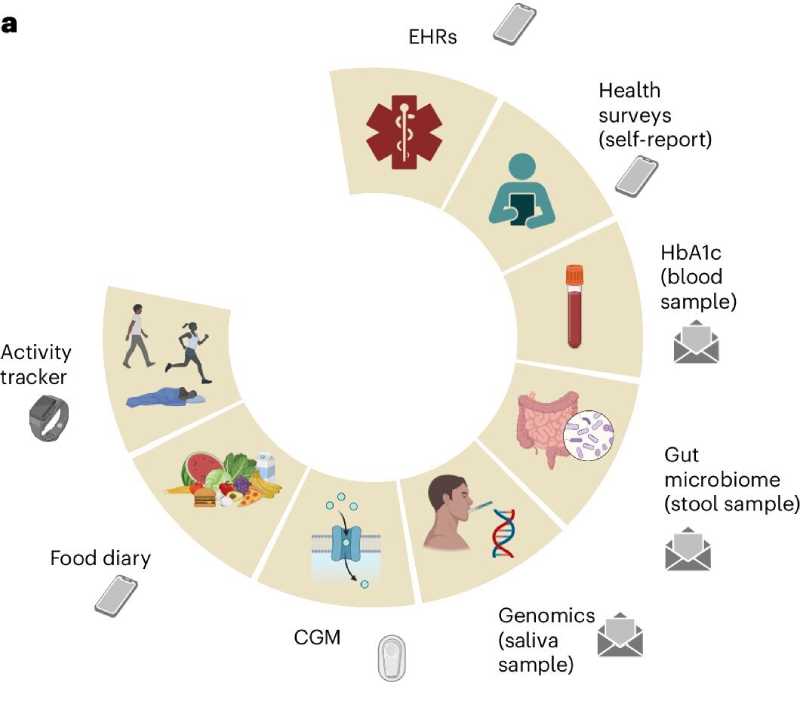

The research used an artificial intelligence–based model and multimodal data — including sleep patterns, diet, heart rate, gut microbiome, and physical activity — to understand glucose behavior across different metabolic profiles. The conclusion: there’s significant variation among individuals with the same HbA1c value, suggesting that this test alone may be insufficient to identify risk.

Of the 1,137 participants, 347 were intensively monitored using continuous glucose sensors, smartwatches, food diaries, and at-home biological sample collection. This approach allowed for accurate tracking of so-called “glucose spikes” — defined as increases of at least 30 mg/dL within 90 minutes.

The analysis showed that people with prediabetes already exhibit significant changes in these spikes, though they more closely resemble normal patterns than those seen in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Among the most variable indicators between groups were the time it took for glucose to return to baseline and the frequency of nighttime hypoglycemia.

One of the most intriguing findings was the link between gut microbiome diversity and glycemic control. The greater the bacterial diversity in the gut, the lower the average glucose levels and time spent in hyperglycemia. Additionally, individuals with higher resting heart rates took longer to stabilize glucose spikes.

Another important finding was the correlation between carbohydrate intake and the peak glucose values. Even more surprising: individuals who consumed more carbohydrates daily tended to “absorb” these spikes more quickly — possibly due to metabolic adaptation.

Regular physical activity had a positive impact on nearly all indicators analyzed. More active individuals showed lower average glucose levels and spent less time in hyperglycemia, regardless of clinical diagnosis. A similar, though smaller, effect was observed with more consistent sleep patterns.

The AI model developed by the researchers was able to accurately classify who had type 2 diabetes and who did not, based on multiple health data points — not just blood tests. When applied to groups with prediabetes, it identified risk profiles that would not have been detected through HbA1c alone.

According to the authors, this multimodal approach could represent a turning point in preventive diabetes care. By offering a more detailed and individualized view, it enables early risk detection and supports personalized interventions — from dietary changes to adjustments in sleep and exercise routines.