Scientists grow pure, stable human mini-kidneys for the first time

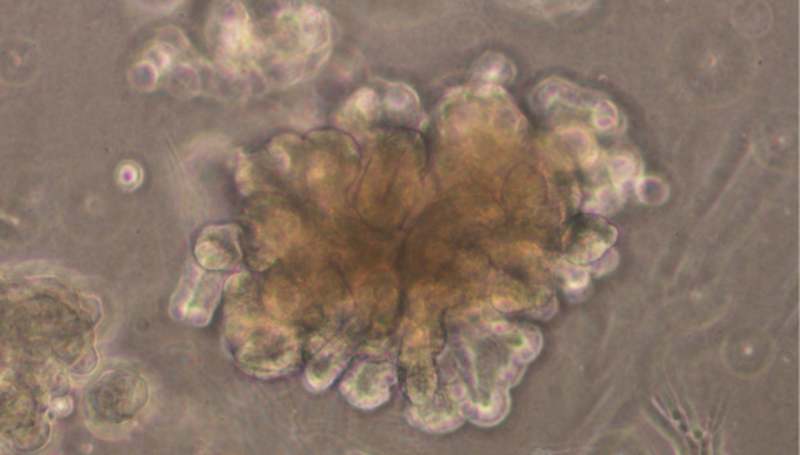

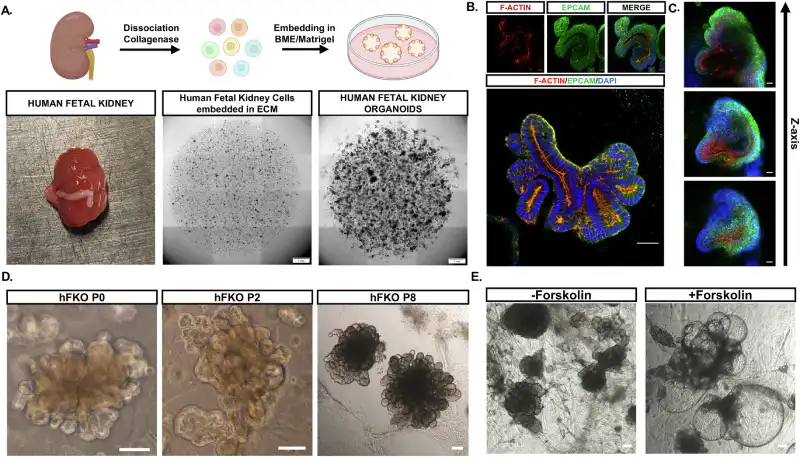

Researchers from Tel Aviv University and Sheba Medical Center achieved an unprecedented feat: creating human mini kidneys — called organoids — in the laboratory from stem cells taken from kidney tissue. These mini organs grew similarly to a developing baby’s kidney in the mother’s womb.

The experiment allowed scientists to observe kidney growth step by step over several months, something impossible to do inside the human body.

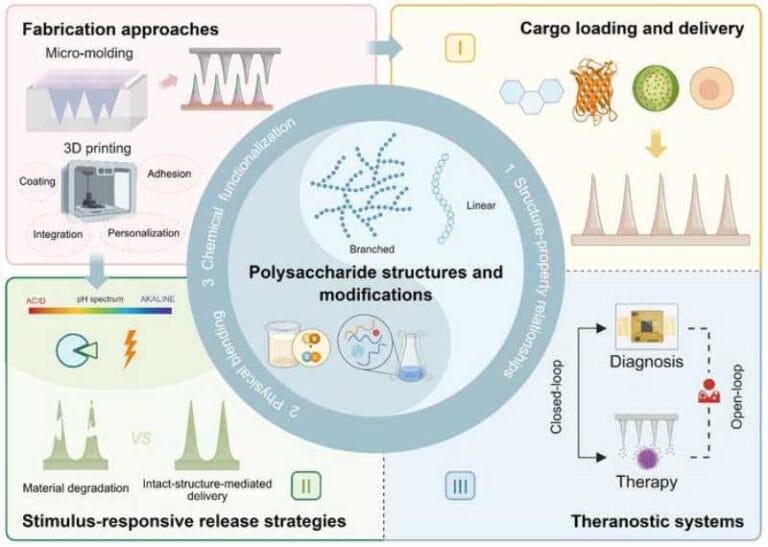

With this, the researchers were able to study how the kidney forms, identify genes that cause birth defects, develop new treatments, and even test whether certain medications might harm babies’ kidneys during pregnancy.

The model created is special for two reasons: it lasted more than six months without breaking down, and it was made solely from kidney cells, without other types of cells mixed in. In previous attempts using another type of stem cell, organoids only lasted four weeks and formed tissues from other parts of the body, which complicated testing.

How it was done

The research was led by Prof. Benjamin Dekel, director of the Sagol Center for Regenerative Medicine and head of the Pediatric Nephrology Unit at Safra Children’s Hospital, Sheba Medical Center. Also involved were Dr. Michael Namestannikov, a doctoral student at Tel Aviv University, and Dr. Osnat Cohen-Sontag, a researcher at Sheba. The work was published in the scientific journal The EMBO Journal.

“Life begins with pluripotent stem cells, which can differentiate into any cell in the body,” explains Prof. Dekel. “In the past, it was possible to grow organoids — three-dimensional cultures resembling organs — by producing these general stem cells and guiding them to form kidneys, but after about a month, the cultivated kidney would die, and the process had to start over. About ten years ago, my research group managed to isolate, for the first time, the stem cells from human kidney tissue responsible for the organ’s growth during development. Now, for the first time, we have been able to cultivate a human kidney in organoid form from these kidney-specific stem cells, tracking the maturation process that occurs in the womb up to the 34th week of gestation.”

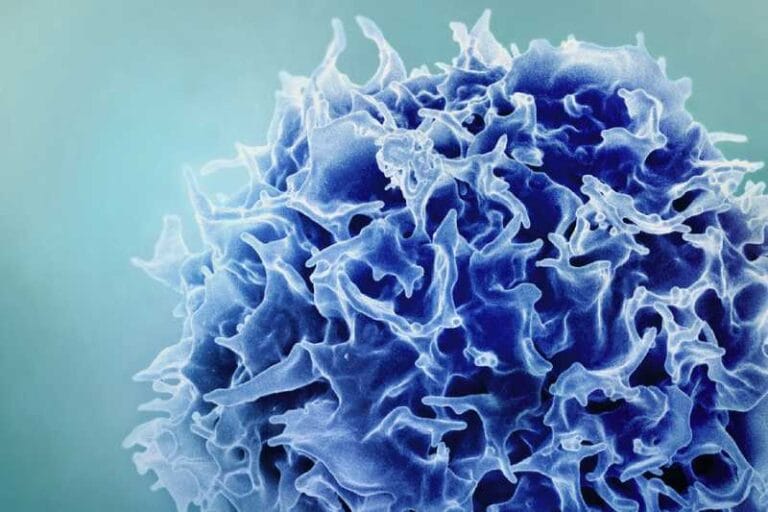

Because these cells are kidney-specific, they transformed only into kidney tissue. Over more than six months of cultivation, they formed different types of kidney cells, such as those that filter the blood, as well as the channels through which urine passes — a process called tubulogenesis.

“Growing fetal kidney structures can shed new light on biological processes in general and, in particular, on those that lead to kidney diseases,” says Prof. Dekel. “In fact, when we selectively blocked certain signaling pathways [in the organoid], we saw how this caused a congenital defect. We are literally watching live how a developmental problem leads to kidney diseases seen in the clinic, which will enable the development of innovative treatments.”

According to Dekel, the breakthrough also paves the way for regenerative medicine. “The fact that we can cultivate stem cells from kidney tissue outside the body for long periods opens the door to regenerative medicine — that is, transplanting kidney tissue grown in the lab into the body or, alternatively, using the signals secreted by the organoid to repair and rejuvenate a damaged kidney. Now we have an almost limitless source of different kidney cells and a deeper understanding of their roles in kidney development and function.”

- See also: New approach to spinal cord injury

For Prof. Dror Harats, chairman of the Sheba Research Authority, the result also underscores Israel’s importance in global science. “In recent years, we have witnessed attempts to sideline Israel from international centers of influence, and scientific successes like this serve as a reminder that our contribution to medical and scientific research is significant and unquestionable.”