Meteoric iron in early Iron Age artifacts in Poland

A recent study led by Dr. Albert Jambon and his team, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, identified meteoric iron in Early Iron Age ornaments from Poland.

Dr. Jambon explained that the research was driven by a quest to understand the origins of iron smelting. “The point of my research is to find out who, when, and where the iron smelting was discovered. To that end, we need to analyze archaeological irons and check whether they are meteoritic or smelted.”

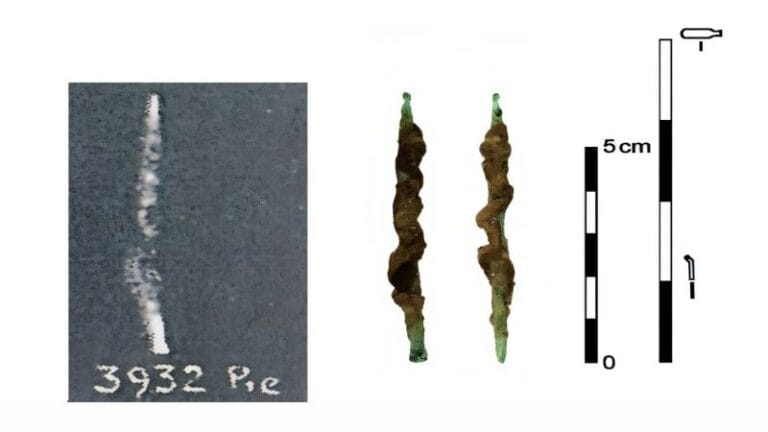

To investigate this, researchers analyzed iron artifacts from two Early Iron Age cemeteries in southern Poland—Częstochowa-Raków and Częstochowa-Mirów—both associated with the Lusatian Culture and dated to the Hallstatt C to C/D period (circa 750–600 BCE). Separated by approximately 6 km, these sites yielded 26 iron artifacts, including bracelets, ankle rings, knives, spearheads, and necklaces.

Using a combination of analytical techniques—such as portable X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray microtomography—the researchers examined the elemental composition and internal structure of the artifacts.

Dr. Jambon and his team identified four artifacts that contained meteoric iron: three bracelets (one of which had been used as an ankle ring) from Częstochowa-Raków and a pin from Częstochowa-Mirów. Despite the limited number of finds, Częstochowa-Raków stands out as one of the most densely concentrated archaeological sites for meteoric iron, rivaling locations in Egypt.

Based on the high nickel content in the iron, the researchers concluded that the artifacts were likely crafted from an ataxite meteorite, a rare type of iron meteorite. Given its scarcity, they proposed that the meteorite must have been sourced locally—unlike terrestrial iron, which was typically imported from the Alps or the Balkans.

“We can conclude that there is a high likelihood that there was a witnessed fall rather than a lucky find. Iron meteorites may be large (hundreds of kg), but this may actually be a problem. Large pieces are not workable, and you need to separate small pieces (less than one kg), which is hardly possible with the tools of the Iron Age (see, e.g., the pieces of iron worked by the Inuits),” Dr. Jambon explains.

“In France, in 1830, a piece of meteoritic iron (about 600 kg) was recognized in front of the church in Caille. There were attempts to take pieces in order to make tools, but the local people gave up, and not a single object of meteoritic iron was recovered.”

“If you go hunting after a fall, you may find many small pieces until they are covered by the vegetation. [A] one kg piece will make a hole in the ground about 20 cm deep. If it rains, which may happen in Europe, such small pieces will never be recovered. Recovering workable pieces is more likely after a witnessed fall.”

Interestingly, iron—even meteoric iron—was not considered a high-value material, even during the Iron Age. This idea is reinforced by the archaeological context in which the meteoric iron artifacts were found: they appeared in the graves of both males and females (including children) and were present in both inhumations and cremations.

The distribution of these artifacts across various burial types suggests that there were no age, gender, or social status restrictions on who could be buried with meteoric iron. Furthermore, none of the graves contained luxury items such as gold, silver, gemstones, or foreign imports, further supporting the notion that meteoric iron was not regarded as particularly prestigious.

“During the Bronze Age, the price of iron was about ten times that of gold; in the early Iron Age, it sank drastically to less than copper,” explains Dr. Jambon.

Interestingly, SEM and CT analyses provided further insights. While it was already known that the meteoric iron had been mixed with slag iron, the analysis revealed faint banding patterns on the metal. Because of its high nickel content, meteoric iron would have appeared white when smelted, contrasting with the black appearance of terrestrial slag iron.

This deliberate mixing of iron sources may have been an intentional technique to create patterned metals. If so, these artifacts would represent the oldest known example of patterned iron—predating the invention of Damascus steel by centuries.