Microplastics May Spread Dangerous Pathogens, Scientists Warn

Scientists are working diligently to assess the scale of microplastic pollution and its potential impacts on human and environmental health. Research suggests that microplastics themselves may be harmful to biological systems and are also known to absorb other toxic pollutants.

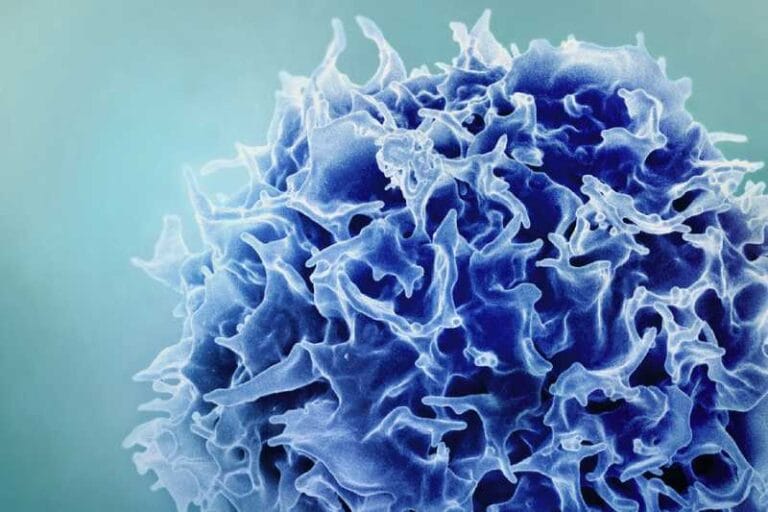

Now, new findings from researchers at the University of Exeter and Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the UK indicate that microbes can develop biofilms on microplastics.

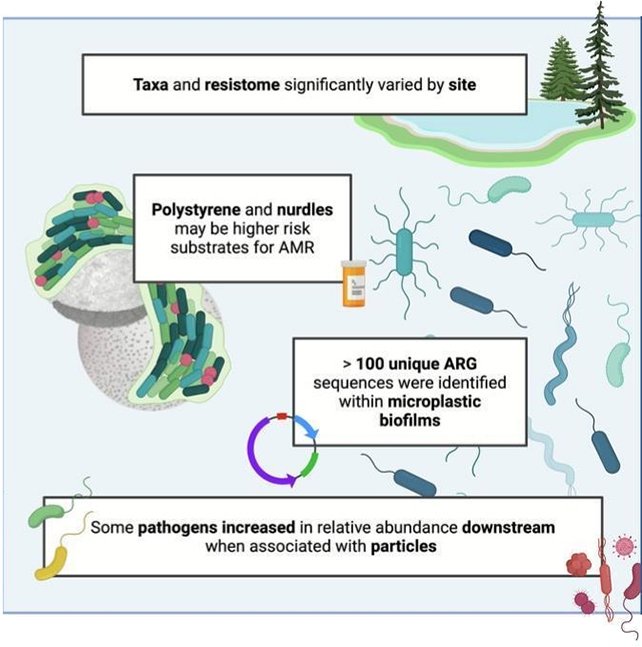

These biofilms, sometimes called “plastispheres,” can harbor dangerous bacteria and promote their growth and survival. This means microplastics could be spreading pathogens and antimicrobial resistance, posing serious health risks—from disease-causing bacteria entering the food chain to an increased spread of drug-resistant bacteria that make infections harder to treat and medical procedures riskier.

“Our research shows that microplastics can act as carriers for harmful pathogens and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, increasing their survival and spread,” said marine scientist Pennie Lindeque of Plymouth Marine Laboratory.

“This interaction represents a growing environmental and public health risk that requires urgent attention.”

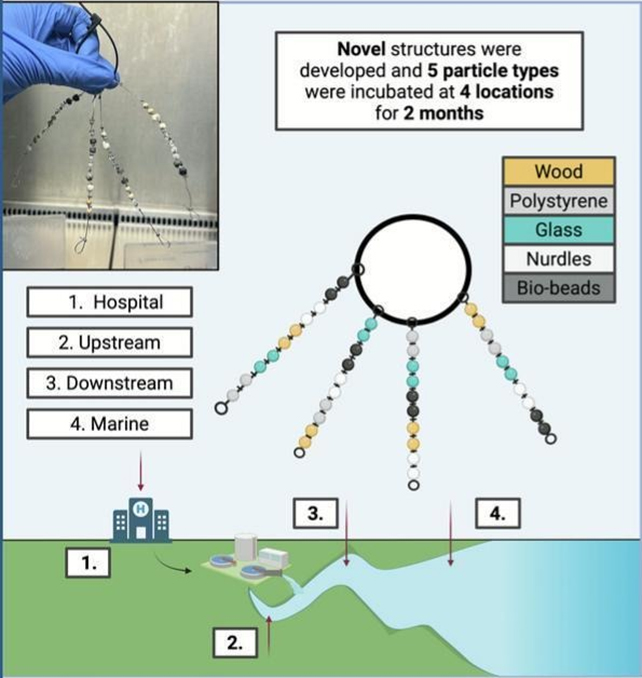

The researchers submerged strings of tiny plastic beads used in manufacturing and water treatment, along with similar-sized polystyrene fragments (around 4 mm), at four sites along the River Truro system in southwest England.

The sampling sites were chosen to represent a range of expected water cleanliness, based on their proximity to a wastewater treatment plant and a hospital.

Small glass and wooden beads were also tested, alongside plastic bio-beads used to host bacteria that help purify water. While these bio-beads are designed to improve the environment, they can cause problems if they escape treatment facilities and enter river systems, which has happened multiple times in the past.

After two months, the team analyzed the bacteria that had accumulated on the various materials. While the sampling location had more influence on bacterial composition than the material type, several concerning trends emerged regarding the plastic particles. Biofilms on microplastics carried significantly more genes for drug-resistant bacteria than those on wood or glass.

Harmful pathogens, including Flavobacteriia and Sphingobacteriia, were also more common on microplastics downstream of the hospital and wastewater treatment plant, where these bacteria were not particularly abundant in the water.

“Our research shows that microplastics are not just an environmental issue—they may also play a role in spreading antimicrobial resistance,” said microbiologist Aimee Murray of the University of Exeter.

“That’s why we need integrated, cross-sector strategies to tackle microplastic pollution and protect both the environment and human health.”

The researchers plan to expand sampling locations and test a wider range of environmental conditions to better understand the impacts. They also emphasize the need to prevent plastics, including bio-beads, from entering the environment.

“This work highlights the diverse and sometimes harmful bacteria that grow on plastic in the environment,” said marine scientist Emily Stevenson of the University of Exeter. She advises that “any volunteers cleaning beaches should wear gloves during cleanups and always wash their hands afterward.”

The study was published in Environment International.