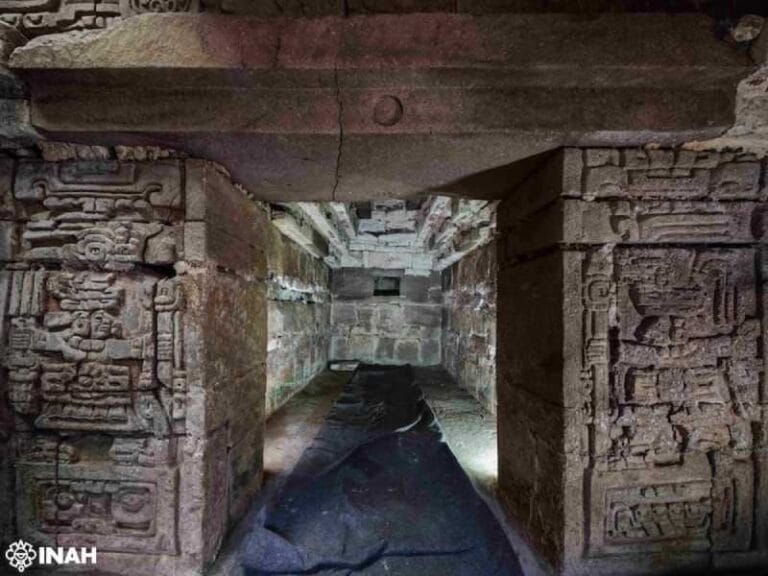

Millennia-old raw clay sculptures in a cave in Mexico

In the heart of the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico, a cave silently held an enigmatic collection of raw clay sculptures. Now, more than a thousand years after they were shaped, these pieces are beginning to reveal their stories through an international study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

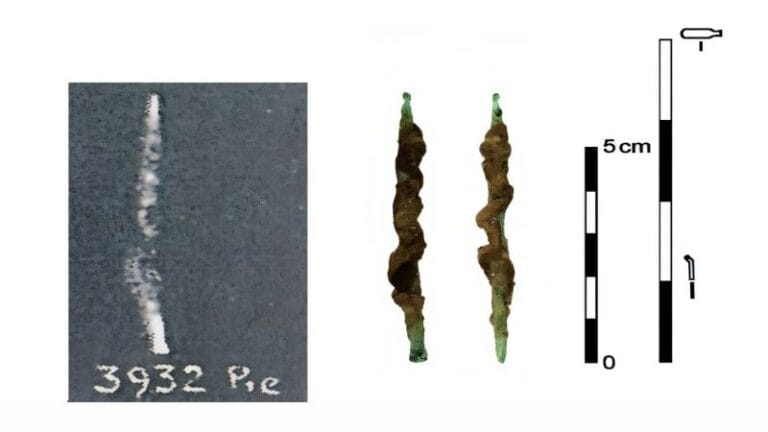

Located in the Sierra Mixe, the Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy — also known as Cueva del Diablo — is home to 72 clay figures, including human and animal forms, as well as miniature structures such as a 3.8-meter-long ballgame court. The sculptures were first discovered in 2011, but only recently underwent a systematic analysis led by archaeologist Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert.

What intrigues researchers the most is that the figures were sculpted using unfired clay. This means that, unlike traditional ceramics, they were not kiln-fired, a process that typically ensures greater durability. Even so, they withstood the test of time thanks to the cave’s stable humidity and temperature—natural conditions that acted like a protective capsule.

Beyond their impressive preservation, the origin of the materials is also noteworthy. The clay used came directly from the cave itself, with no added sand or ash. Local sediments, rich in mica and quartz, provided structural strength to the figures. In some sculptures, such as jaguar heads, black stains reveal the use of manganese oxides as pigment, also collected from within the cave.

The variety and richness of the depicted themes suggest a symbolic rather than utilitarian purpose. Human figures—men, women with clearly marked genitalia, and children—appear in seated or reclining positions. Animals like jaguars, monkeys, and reptiles are sculpted with remarkable detail, while charcoal fragments associated with the artworks have been radiocarbon dated to between A.D. 607 and 881, corresponding to the Late Classic period of Mesoamerica.

The presence of an older piece of charcoal, dated between 151 B.C. and A.D. 8, indicates that the cave had been in use long before these sculptures were created. For archaeologists, this detail points to prolonged occupation, with possible distinct phases of artistic production over the centuries.

When analyzing the modeling techniques, researchers observed that the clay was handled with minimal pressure. There was no vigorous kneading—the artists skillfully took advantage of the material’s natural plasticity, which was enhanced by the cave’s humid climate. In some cases, stones and broken stalactites were used to support heavier parts of the sculptures, such as heads or torsos.

Although the authors of the study cannot yet confidently attribute the figures to a specific culture, the temporal evidence coincides with the rise and fall of urban centers such as Monte Albán and Teotihuacán. This raises the hypothesis that the works may have been created by a peripheral cultural group, or even one not yet documented.