New “terror birds” discovered in South America

Scientists have identified a new species of the massive avian predators known as “terror birds,” which once roamed the South American landscape in search of prey. The discovery was made through the analysis of a fossilized leg bone found two decades ago, which has now been confirmed as the lower leg bone of a Phorusrhacidae. Researchers estimate that this ancient bird stood nearly ten feet tall, making it the largest known specimen of this extinct species.

The study, led by terror bird specialist Federico J. Degrange and Siobhán Cooke, Ph.D., associate professor of functional anatomy and evolution at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, also revealed that this newly identified terror bird fossil is the northernmost example found in South America.

The bone was first unearthed nearly 20 years ago by Cesar Augusto Perdomo, curator of the Museo La Tormenta in Colombia’s Tatacoa Desert, located at the continent’s northern tip. Given the abundance of fossils in the area, Perdomo did not initially realize that the bone belonged to this formidable predator.

Cooke explains that these carnivorous terror birds shared their habitat with a variety of other creatures, including primates, hoofed mammals, giant ground sloths, and even glyptodonts—car-sized relatives of modern armadillos. Although the recent analysis of the bone doesn’t indicate which of these animals the terror bird preyed upon, Cooke suspects that this wingless predator was likely willing to hunt and eat nearly any creature it encountered.

“Terror birds lived on the ground, had limbs adapted for running, and mostly ate other animals,” Cooke explained.

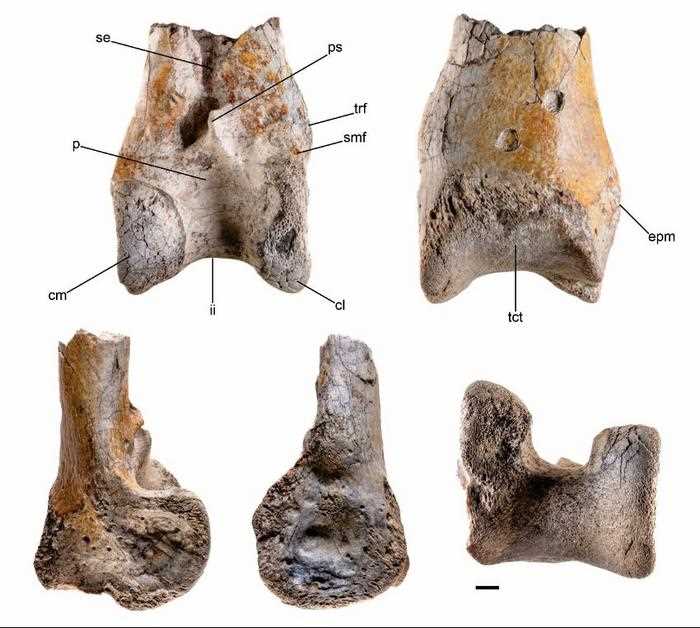

Using a portable scanner, the researchers created a detailed three-dimensional virtual model of the fossilized leg bone, allowing for an in-depth analysis. The scans revealed pitting on the bone’s surface, a distinctive feature confirming it belonged to a terror bird.

The team also discovered what appeared to be tooth marks likely left by a distant relative of the alligator, the caiman. The severity of these marks suggests they may have even contributed to the massive predator’s death.

“We suspect that the terror bird would have died as a result of its injuries given the size of crocodilians 12 million years ago,” Cooke explained.

Given the rarity of terror bird fossils, the team believes these predators may have been relatively “uncommon” across the South American landscape. However, they also suspect that other fossils might already have been discovered but remain unidentified, possibly due to being smaller or less complete than this sample.

“It’s possible there are fossils in existing collections that haven’t been recognized yet as terror birds because the bones are less diagnostic than the lower leg bone we found,” Cooke explained.

The team considers the discovery of this particular terror bird so far north to be significant, especially as it may represent the largest specimen of its species ever found. For Cooke, uncovering evidence of this massive predator that roamed the Colombian desert over 12 million years ago provides scientists with a rare glimpse into the ancient landscape of South America.

“It’s a different kind of ecosystem than we see today or in other parts of the world during a period before South and North America were connected,” she said. “It would have been a fascinating place to walk around and see all of these now-extinct animals.”

The study was published in the journal Palaeontology.