New method of producing human cartilage

Recent discoveries reveal a significant advance in the artificial generation of human cartilage for the head and neck region, promising potential benefits for those facing degenerative joint diseases and other disorders.

The new method of producing cartilage comes as a result of the efforts of a team of researchers and collaborators at the University of Montana. This innovation, with the potential to revolutionize treatments, is especially aimed at individuals with injuries that affect cartilage or suffer from degenerative conditions.

Each year in the United States, approximately 230,000 children are born with craniofacial defects, highlighting the urgency for viable solutions given that natural cartilage regeneration is challenging in the human body.

According to Mark Grimes, professor of biology in the Division of Biological Sciences at the University of Montana, critical demand drove the team to develop an innovative, stem cell-based method capable of generating cartilage cells specific to the human face and neck.

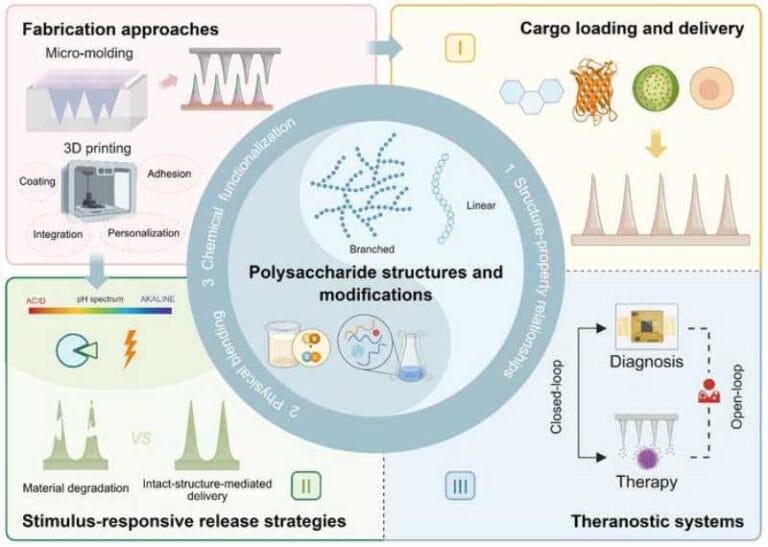

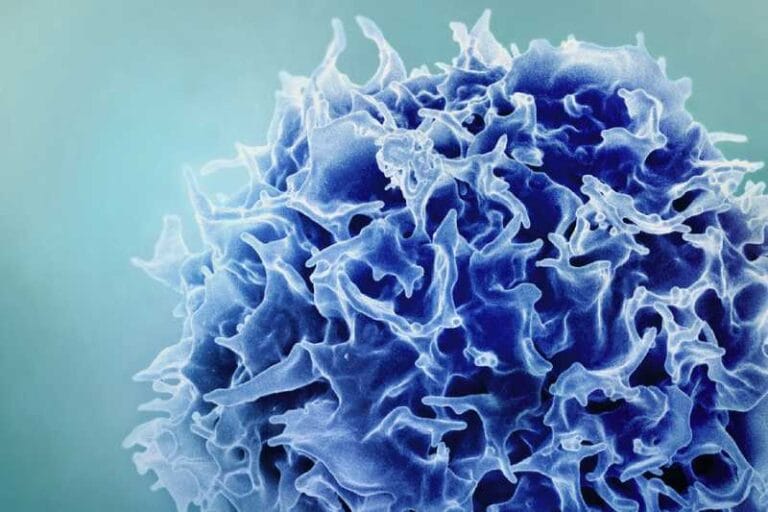

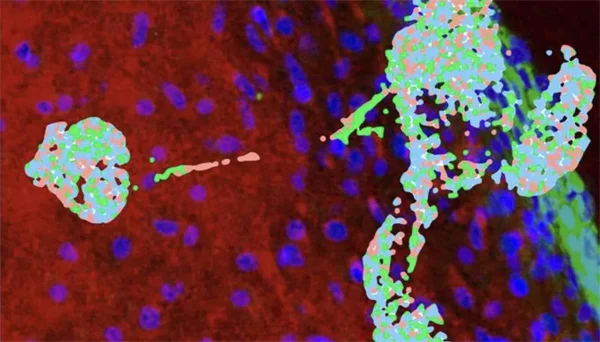

Grimes highlights the success in using neural crest cells to create a new means of producing craniofacial organoids, replicating the main functions, structure and biological complexity of miniature organs, under controlled laboratory conditions. This advance represents a promising alternative, moving away from the dependence on embryonic stem cells in previous organoid production processes.

“Organoids are a good model for certain human tissues that we can study in ways that are not possible using tissues from humans,” Grimes said in a statement.

Grimes and his team delved into gene expression data related to RNA proteins, aiming for a deeper understanding of the process of stem cell differentiation into cartilage cells. This effort revealed the intricate mechanisms of communication between stem cells during their early stages of development toward the type of cartilage present in our ears.

Using machine learning techniques, the team analyzed biological markers and distinctive patterns, providing valuable insights into cell signaling pathways crucial to the initial transition toward cartilage formation.

However, a significant challenge associated with the use of artificial cartilage sources is the tendency of the human body to reject transplanted tissue, often requiring the use of immunosuppressive medications to facilitate these procedures.

“To use patient-derived stem cells to generate craniofacial cartilage in the laboratory, we must understand human-specific differentiation mechanisms,” Grimes explained in a recent statement, adding that he and his colleagues hoped to find a method of producing cartilage. craniofacial tissue that was more suitable for transplant surgery using stem cells.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Grimes and his team’s findings were highlighted in a new paper titled “Craniofacial Chondrogenesis in Organoids from Human Stem Cell-Derived Neural Crest Cells,” recently published in the journal iScience.