Orangutan seen treating wounds with medicinal plants

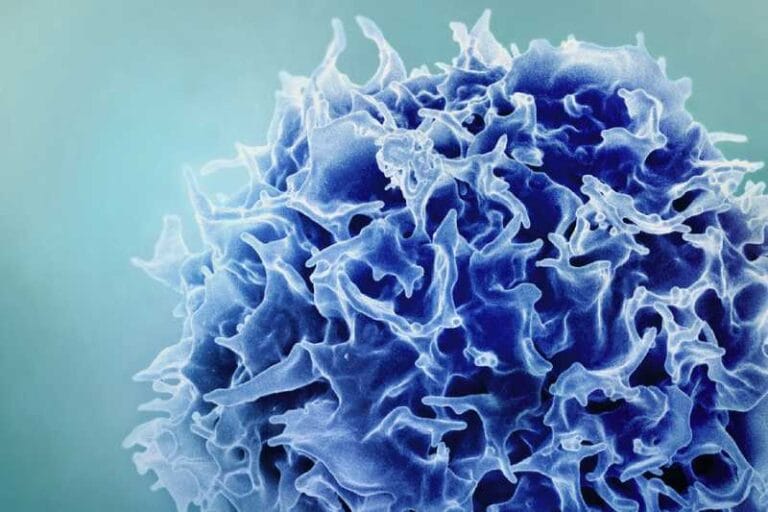

Rakus, the resident orangutan of Gunung Leuser National Park in South Aceh, Indonesia, amazes scientists at the Institute of Animal Behavior with his remarkable command of first aid. Scientists such as Caroline Schuppli, an evolutionary biologist, and Isabelle Laumer, a cognitive biologist, study the park’s animals closely, recording their activities every two minutes.

During an observation of Rakus, the team led by Schuppli and Laumer noticed a significant facial wound. They suspect that the wound was the result of a confrontation with another male during a “long call battle”. In these episodes, adult male orangutans, such as Rakus, emit prolonged vocal calls to attract females and demarcate territory, but sometimes these calls can also attract physical confrontations with rival males.

The research team identified a sequence of long calls before noticing Rakus’ injury, suggesting his participation in one of these territorial disputes. Rakus’ ability to survive and cope with injuries of this kind highlights his adaptability and intelligence, surprising the researchers with his apparent understanding of the basic principles of medical care.

Just three days after the incident that injured him, Rakus began an exceptional behavior: he started feeding on a liana known as Akar Kuning, a plant with powerful medicinal properties that is not part of the orangutan’s usual diet. The scientists observed Rakus chewing the leaves and then applying them directly to his wound, using his own finger as a tool. This demonstration of self-care and use of natural resources to promote healing is a remarkable example of the adaptive intelligence of these primates.

“This was, to our knowledge, the first time that a wild animal applied a potent healing plant to his own wounds,” Laumer said.

Self-medication is rare among animals

Scientists have witnessed self-medication behavior in animals before. For example, a group of chimpanzees in Gabon were seen applying insects to their wounds.

However, scientists have yet to determine whether these insects have any real medicinal properties. As Laumer pointed out, “therefore, we don’t know if this behavior is in any way effective or functional”. In other words, it’s not clear whether the chimpanzees’ behavior is intentional.

What distinguishes what Rakus did are some important nuances.

Rakus made an unusual choice, opting for a plant that is rarely part of his species’ diet. What’s more, he applied the crushed leaves directly to his wound, indicating a conscious selection of treatment. During this period, he also spent more than half the day resting, a behavior that can favor the wound healing process.

The most significant aspect, however, is that his treatment proved to be effective.

“The wound healing was quite rapid, Laumer said. “Within four days, the wound was closed, and there are no signs of any infection.”

This evidence points to the possibility that this behavior was an intentional form of self-medication on the part of Rakus.

As Laumer noted, witnessing something like this in the wild is extremely unusual. This type of behavior is usually associated with ancient and highly evolved species. In addition, researchers need to be in the right place at the right time to witness such a phenomenon.

Had he learned this skill?

The origin of the behavior observed in Rakus, where he seems to intentionally apply medication to his wound, remains an intriguing mystery. As Laumer pointed out, there are some plausible explanations, but it is difficult to determine with certainty the reason behind this innovative behavior.

One possibility is that Rakus performed an individual innovation, a phenomenon in which an animal invents a new behavior for the first time. In this case, it may have been an initial accident.

Another explanation is that Rakus discovered the medicinal properties of the plant accidentally, by involuntarily touching his leaf-covered finger to his wound and feeling the analgesic effects. This positive feedback could have motivated him to repeat the behavior.

A third possibility is that Rakus learned this behavior by observing other orangutans. Orangutans are known to be able to learn socially, often by observing and imitating members of their group, especially during the first years of life, when the cubs peek at their mothers to learn survival skills.

However, as this is the first record of this behavior in orangutans, scientists cannot yet definitively determine its cause or origin. The mystery surrounding Rakus’ behavior highlights the complexity and fascinating nature of animal intelligence.

The behavior observed in Rakus remarkably echoes our own practices of using medicinal plants, which suggests a deep and lasting connection between the species. This similarity leads us to reflect on the possible origin and evolution of our ability for medicinal treatments.

Considering that our oldest shared ancestor with orangutans dates back more than 10 million years, it is plausible that this type of behavior has its roots in the distant past. If Rakus is demonstrating a primitive form of self-medication, this suggests that such behavior may have developed over millions of years of shared evolution between humans and orangutans.

“It also shows how similar we are, more similar than we are different,” Laumer said. “It points to how amazing and incredibly smart these animals are, and how important it is to protect them.

They published their findings in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.