Persian goddess temple discovered in Iraqi Kurdistan

A team of archaeologists carried out excavations at the mountain fortress of Rabana-Merquly, located in present-day Iraqi Kurdistan, and proposed that the site could also have functioned as a sanctuary dedicated to the Persian water goddess Anahita.

Rabana-Merquly is an archaeological site located in the Zagros Mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, on the slopes of Mount Piramagrun. This fortified stronghold is made up of perimeter defenses that surround neighboring settlements in the Rabana valley and Merquly plateau. The main occupation of the Parthian Empire period dates back to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC

According to Dr. Michael Brown, a researcher at the Institute for Prehistory, Protohistory and Ancient Near Eastern Archeology at the University of Heidelberg, a place of worship may have existed at the archaeological site where architectural structures were found near a natural waterfall and traces of a supposed fire altar. Dr. Michael Brown led excavations at the site for several years.

Since 2009, an international team of researchers has explored the archaeological ruins of Rabana, an ancient Parthian settlement. Between 2019 and 2022, they intensified excavations and revealed new discoveries.

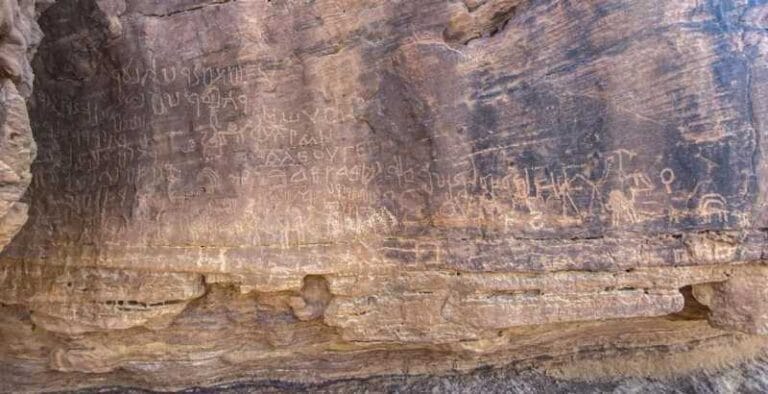

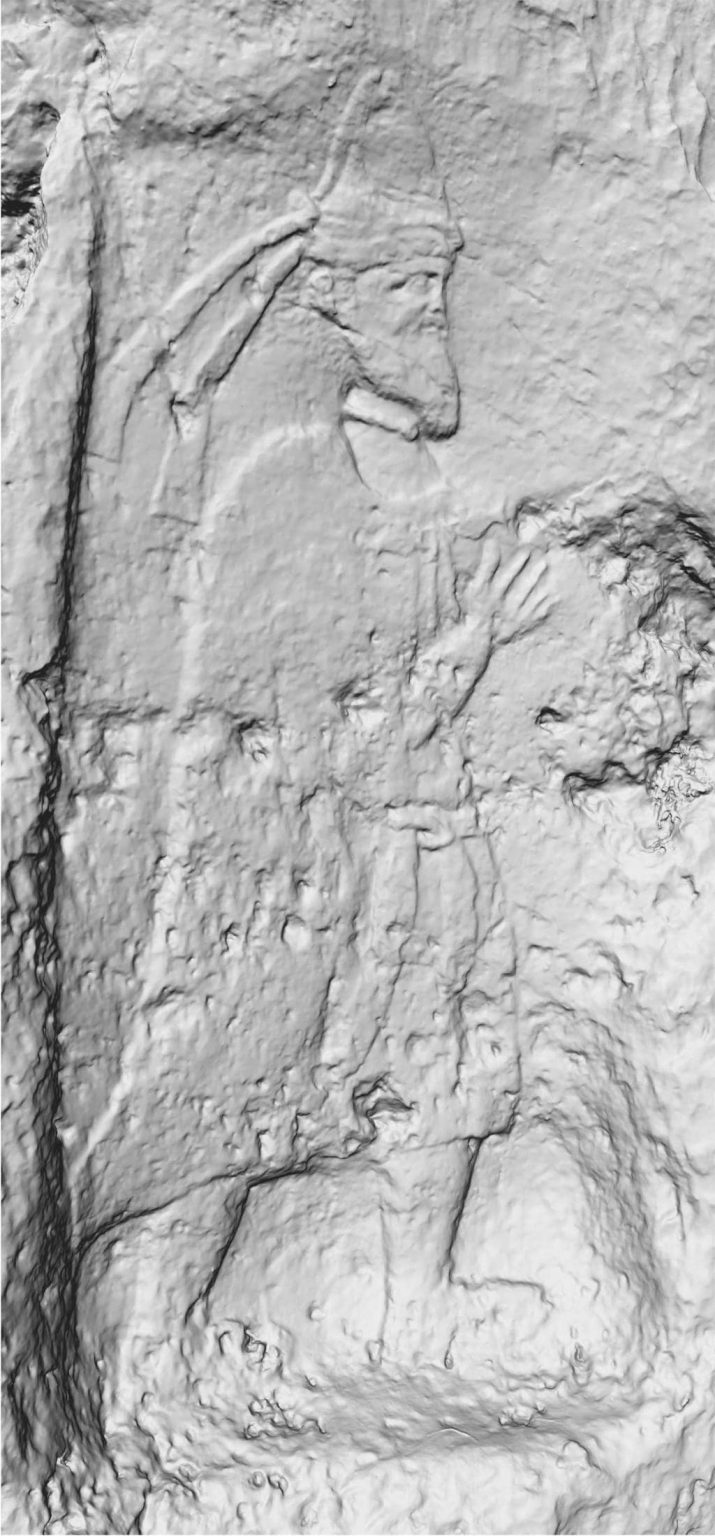

At the fortified entrance to Rabana, a relief carved into the rock shows a mysterious ruler, who may have been a Parthian king subordinate to the Arsacids. He is considered the founder of the place. In the Rabana valley, researchers found a sanctuary that was perhaps dedicated to the goddess Anahita, the deity of water and fertility.

The goddess Anahita, first mentioned in the sacred manuscripts of the Zoroastrian religion called Avesta, is revered as the deity of celestial waters. She is described as a woman of incomparable beauty, with the ability to take the form of a stream or waterfall. During the Seleucid and Parthian periods, the cult of Anahita was widely venerated in the western regions of Iraq.

Inland from Rabana, attention focused on the northeast zone, where a wadi crosses the valley through a narrow gorge high on the mountain. After heavy rains and the melting of snow, an ephemeral waterfall appears, the base of which is adorned by monumental stone architecture. Next to this formation, a small altar, possibly dedicated to fire, was carefully excavated in a sub-rectangular niche in the escarpment. The overall impression is that of a complex of sanctuaries, with the presence of water suggesting a cultic connection to the goddess Anahita.

Therefore, the central evidence supporting the theory that a possible sanctuary dedicated to Anahita was integrated into the mountain fortress of Rabana-Merquly comes from the discovery of architectural structures in the vicinity of a seasonal waterfall within the complex.

“The proximity of the waterfall is significant because the association of the elements of fire and water played an important role in pre-Islamic Persian religion,” said Michael Brown.

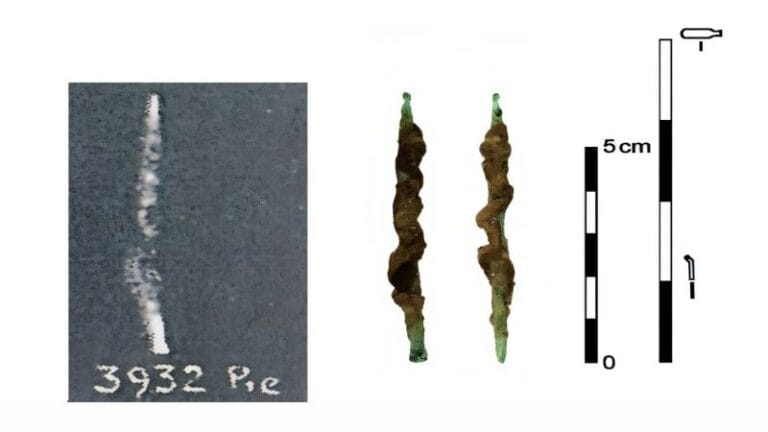

At the archaeological site of Rabana, building remains revealed the presence of two distinct funerary vessels, radiocarbon dated to the 2nd to 1st centuries BC. This discovery suggests that the sanctuary was in use when the fortified settlements of Rabana and Merquly were established.

According to Dr. Brown, it is possible that there was a pre-existing sanctuary, which was later incorporated into the cult of Anahita during the Parthian era. This integration may have played a fundamental role in the occupation of the mountain.

Dr. Brown supports the hypothesis that a pre-existing sanctuary may have been assimilated into the cult of Anahita during the Parthian era. This fusion may have played a crucial role in the occupation of the mountain. At that time, many religious sites also served as places of dynastic worship, honoring both the king and his ancestors. This interpretation is shared by the archaeologist at the University of Heidelberg.

“Even though the place of worship cannot be definitively attributed to the water goddess Anahita, due to the lack of similar archaeological finds for direct comparison, the sanctuary of Rabana continues to provide us with a fascinating glimpse into regional sacral and geopolitical interconnections during the era Leave,” said Dr. Brown.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

The article was published in Iraq magazine . DOI: 10.1017/irq.2023.6