Sanctuary of Apollo rediscovered in Cyprus

Archaeologists have unearthed a long-forgotten sanctuary dedicated to the god Apollo, hidden for nearly 140 years near the ancient city-kingdom of Tamassos in Cyprus. First excavated in 1885 by German archaeologist Max Ohnefalsch-Richter, the site faded into obscurity after being backfilled—its location and significance buried by time.

Now, the sanctuary has been rediscovered in the Frangissa Valley near the village of Pera Orinis. Once among the most affluent rural sanctuaries in the region, it had yielded hundreds of votive statues—including some of colossal proportions—and fully exposed structural remains before disappearing from the archaeological record.

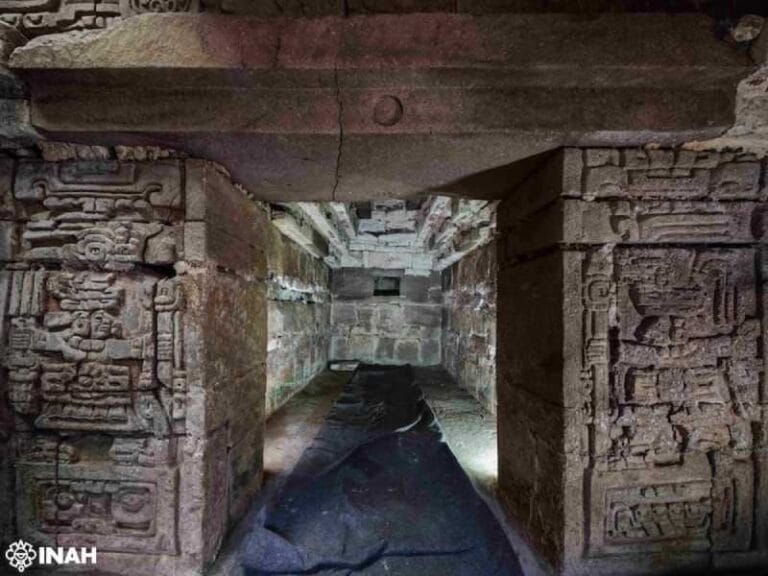

That changed in 2021, when a team from the Universities of Frankfurt and Kiel/Würzburg, led by Matthias Recke and Philipp Kobusch, resumed investigations. In 2024, large-scale excavations revealed extensive architectural remains: foundational walls, a dedication courtyard, and over 100 statue bases—many of them from massive figures.

According to the Republic of Cyprus Department of Antiquities, the excavation yielded more than just bases. Archaeologists recovered a wealth of statue fragments overlooked in the 19th-century dig. “It was found that the 19th-century fill contained not only the bases of the votive statues but also many statue fragments. It seems that, in 1885, in the rush to find impressive discoveries, these were not identified as artifacts,” noted the Excavation Committee of the Department of Antiquities (EK/IA/GS).

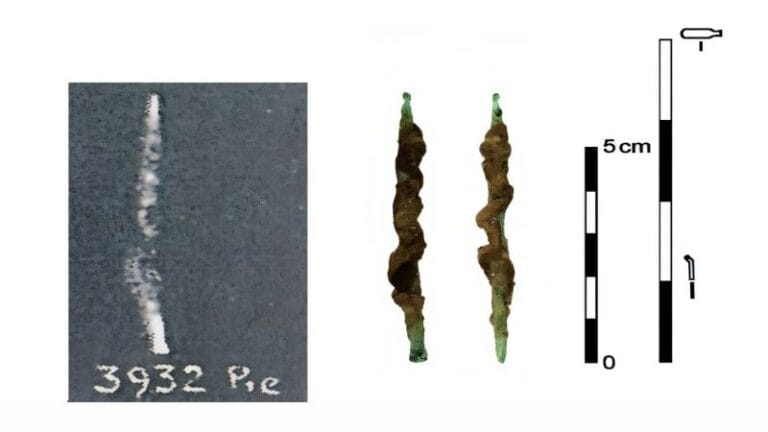

These newly uncovered fragments may allow researchers to reconstruct long-incomplete statues currently housed in the Cyprus Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Among the most striking finds are parts of limestone statues with enormous feet, pointing to the presence of monumental male figures from the Archaic period (7th–6th centuries BCE). Previously, only terracotta colossi, such as the famous “Colossus of Tamassos,” had been documented at the site.

Beyond sculptures, the sanctuary yielded a trove of votive offerings never before recorded at Frangissa. These include Egyptian faience amulets—used in sacred rituals—and marble glass beads, indicating vibrant cross-cultural connections and underscoring the sanctuary’s broader religious and international significance.

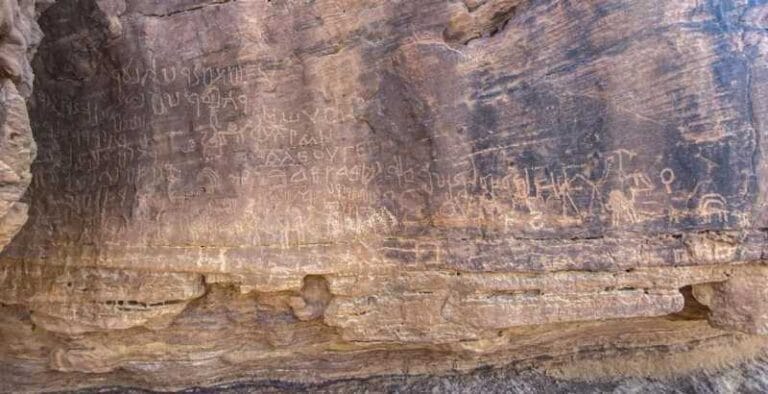

Two statue bases bear inscriptions that enrich the site’s historical narrative: one in local Cypro-Syllabic script and another in Greek, referencing the Ptolemies—the Hellenistic rulers of Egypt and Cyprus after the decline of the island’s city-kingdoms. These inscriptions confirm that the sanctuary remained in use well beyond the Archaic period, thriving into the Hellenistic era.

Evidence also points to major architectural enhancements during this later phase, including the construction of a vast peristyle (colonnaded) courtyard likely used for ritual feasts or symposia. This addition suggests that the sanctuary functioned not only as a religious site but also as a venue for ceremonial and social gatherings.

Crucially, the rediscovery gives archaeologists a rare opportunity to document structural elements neglected during the 19th-century excavation. With the benefit of modern methods, the renewed exploration of the Apollo Sanctuary at Frangissa is rewriting a vital chapter in Cypriot archaeology—one that weaves together sacred ritual, monumental art, and cross-cultural exchange in a sanctuary lost to time but never forgotten.

Sources: Republic of Cyprus, Archaeology Mag.