SPHERE Debris Disk Gallery: Revealing Clues of Dust and Small Bodies in Distant Solar Systems

Observations made with the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope have produced an unprecedented gallery of “debris disks” in exoplanetary systems. Gaël Chauvin (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy), SPHERE project scientist and co-author of the paper presenting the results, states: “This dataset is an astronomical treasure. It provides exceptional insights into the properties of debris disks and allows us to infer the existence of smaller bodies, such as asteroids and comets, within these systems — something impossible to observe directly.”

In our own Solar System, when we look beyond the Sun, the planets, and dwarf planets like Pluto, we find an impressive variety of smaller bodies. A point of great interest is the larger small bodies, with diameters between roughly one kilometer and a few hundred kilometers. We call these objects comets when they (at least occasionally) exhibit gas and dust loss that forms characteristic visible structures, such as a tail; and asteroids when this does not occur. Small bodies offer a glimpse into the earliest history of the Solar System: in the evolution from dust grains to fully formed planets, the small bodies known as planetesimals represent a transitional phase — and asteroids and comets are remnants of that stage, planetesimals that never evolved into larger planets. In other words, small bodies are (slightly) modified vestiges of the material that gave rise to planets like Earth!

Small bodies around stars beyond the Sun?

So far, astronomers have detected more than 6,000 exoplanets — that is, planets orbiting stars other than the Sun — which gives us a much clearer sense of the diversity of planets that exist and where our Solar System fits within this vast population. However, obtaining actual images of these planets is a considerable challenge. At present, there are fewer than 100 exoplanets that astronomers have been able to image, and even giant planets appear only as tiny, detail-less blobs. “Finding any direct clue about small bodies in a distant planetary system from images seems absolutely impossible. And the other indirect methods used to detect exoplanets don’t help either,” says Dr. Julien Milli, an astronomer at the University of Grenoble Alpes and co-author of the study.

Ironically, the solution comes from something even smaller — several orders of magnitude smaller. Especially in young planetary systems, planetesimals collide regularly — sometimes merging to form larger bodies, sometimes breaking apart. These collisions produce huge amounts of fresh dust, and, as it turns out, this dust can be observed from great distances when we have the right instruments: whenever you break an object into smaller components, the total volume stays the same, but the total surface area increases. Break apart a one-kilometer asteroid into micrometer-sized dust grains (= one millionth of a meter), and the total surface area increases by a factor of a billion! This is largely why it is possible to observe debris disks around young stars via reflected starlight. Observe the dust, and you can gather information about the small bodies in the planetary system.

Observing Debris Disks

As time goes by, a debris disk like this gradually weakens. Collisions become less frequent. The dust is expelled from the system by radiation pressure, captured by planetesimals or planets, or ends up falling into the central star. Our own Solar System offers an example of what remains after billions of years: in this case, two belts of leftover planetesimals still exist — the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and a reservoir of comets beyond the orbits of the giant planets, known as the Kuiper Belt. There is also dust in the main orbital region of our Solar System, called zodiacal dust. Under a very dark sky, it is possible to see the light reflected by this dust with the naked eye, just after sunset or shortly before dawn — the so-called “zodiacal light.”

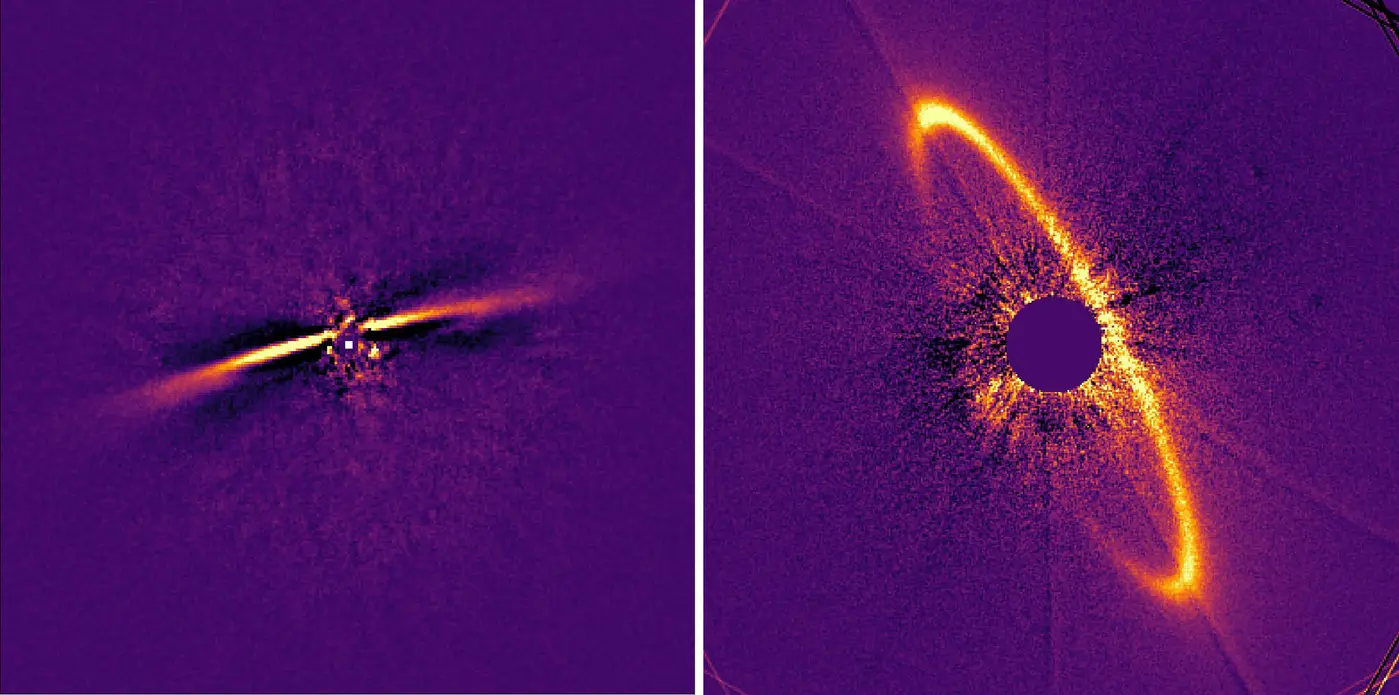

This configuration would be difficult for alien astronomers studying our Solar System from afar to detect. But, as the current study shows, with the best available telescopes and instruments, in relatively nearby systems, this dust should be observable for roughly the first 50 million years of a debris disk’s lifetime. That does not mean such observations are not a major technical challenge! Observing a debris disk is like trying to photograph a cloud of cigarette smoke next to a stadium spotlight — and you’re taking the picture from several kilometers away. This is where the right instrumentation makes all the difference, and where the SPHERE instrument, which began operating on one of ESO’s Very Large Telescopes (VLT) in the spring of 2014, truly stands out.

Blocking starlight

At the heart of SPHERE lies a very simple concept. In everyday life, if we want to look at something but the Sun in the background gets in the way, we block the light with our hand. When SPHERE observes an exoplanet or a debris disk, it uses a coronagraph to block the star’s light — essentially, a small disk inserted into the optical path that removes most of the starlight before the image is recorded. The issue is that unless the image is extremely precise and stable, this simple solution does not work in practice!

To meet these strict requirements, SPHERE uses an extreme version of adaptive optics, in which the inevitable distortions caused by light passing through Earth’s atmosphere are analyzed and largely corrected in real time through the use of a deformable mirror. Another optional component of SPHERE filters light with specific properties (“polarized light”), characteristic of light reflected by dust particles — in contrast to starlight — paving the way for highly sensitive images of debris disks.

An unprecedented gallery of debris disk images

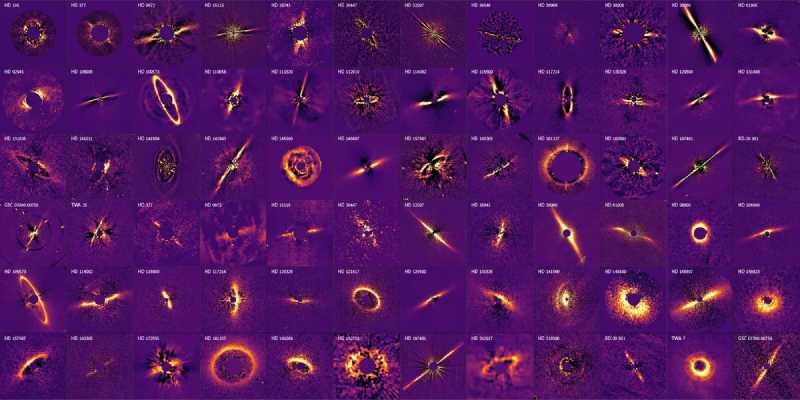

The new publication presents a unique collection of debris disk images produced with SPHERE from starlight reflected by tiny dust particles in these systems. “To obtain this collection, we processed observation data from 161 nearby young stars whose infrared emission strongly indicates the presence of a debris disk,” says Natalia Engler (ETH Zurich), the study’s lead author. “The resulting images show 51 debris disks with a variety of properties — some smaller, others larger, some seen edge-on, others nearly face-on — and a considerable diversity of structures. Four of these disks had never been imaged before.”

Comparisons within a larger sample are crucial for uncovering systematic patterns behind the properties of these objects. In this case, an analysis of the 51 debris disks and their stars confirmed several trends: when a young star is more massive, its debris disk also tends to have more mass. The same is true for disks in which most of the material is located farther from the central star.

Finding Asteroid Belts and Kuiper Belts in Other Systems

Possibly the most intriguing aspect of the debris disks observed by SPHERE is the structures within them. In many of the images, the disks display concentric ring- or band-like structures, with material concentrated at specific distances from the central star. The distribution of small bodies in our own Solar System shows a similar pattern, with bodies concentrated in the asteroid belt and in the Kuiper Belt.

All these belt-like structures appear to be associated with the presence of planets — specifically giant planets — that “clear out” their surroundings of smaller bodies. Some of these giant planets had been observed previously. In some of the SPHERE images, features such as sharp inner edges or asymmetries in the disk offer intriguing clues to planets that have not yet been detected. In this way, the collection of disks obtained by SPHERE identifies promising targets for future observations: the JWST and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), currently under construction by ESO, are expected to allow astronomers to image the planets responsible for these structures.

Additional information: The results described here were published by Natalia Engler et al., “Characterization of debris disks observed with SPHERE,” in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554953

The MPIA researchers involved are Gaël Chauvin, Thomas Henning, Samantha Brown, Matthias Samland, and Markus Feldt, in collaboration with Natalia Engler (ETH Zürich), Julien Milli (CNRS, IPAG, Université Grenoble Alpes), Nicole Pawellek (University of Vienna), Johan Olofsson (ESO), Anne-Lise Maire (CNRS, IPAG, Université Grenoble Alpes), and others.