Discovered: Tomb of the First King of Caracol, Ancient Maya City

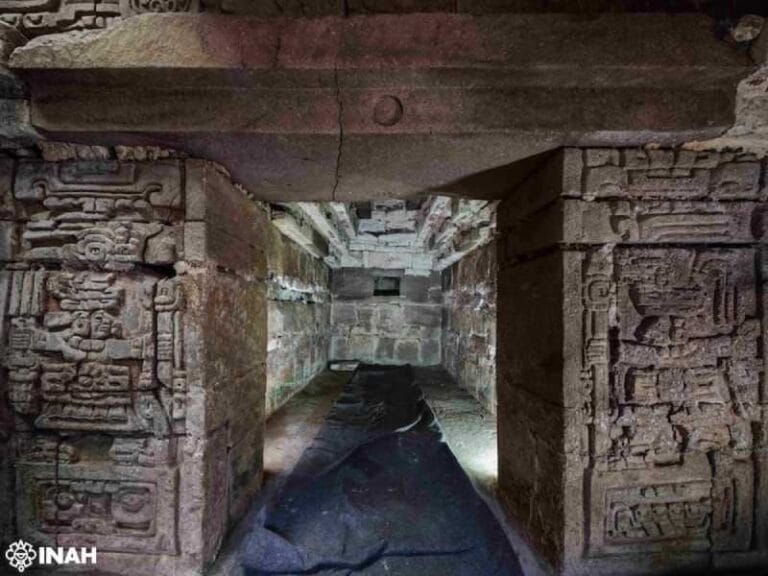

Archaeologists from the University of Houston have announced the discovery of the tomb of Te K’ab Chaak, the first ruler of the Maya city of Caracol in Belize. The identification of the burial marks a major milestone: it is the first royal tomb recognized in over 40 years of excavations at the country’s largest Maya archaeological site.

Te K’ab Chaak was buried around 331 A.D. at the base of a royal family shrine. Alongside him were ceramic vessels, carved bone tubes, jadeite jewelry, Pacific shells, and an impressive jadeite mosaic mask. Analysis of the skeleton indicates that the king was about 5 feet 7 inches tall, elderly at the time of death, and had no remaining teeth.

The vessels found in the burial chamber drew attention for their rich symbolism. One depicts a ruler holding a spear and receiving offerings from deities. Another shows the image of Ek Chuah, the Maya god of commerce, surrounded by offerings. Four vessels portray bound captives, and two had lids modeled with the heads of coatimundi, animals that later appeared in the names of other Caracol kings.

The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak is part of a set of three burials dated to around 350 A.D., all located in the Northeast Acropolis of the city. A second burial, discovered in 2010, was an unusual cremation positioned in the center of a residential plaza — an atypical practice among the Maya, but common in Teotihuacan, in central Mexico.

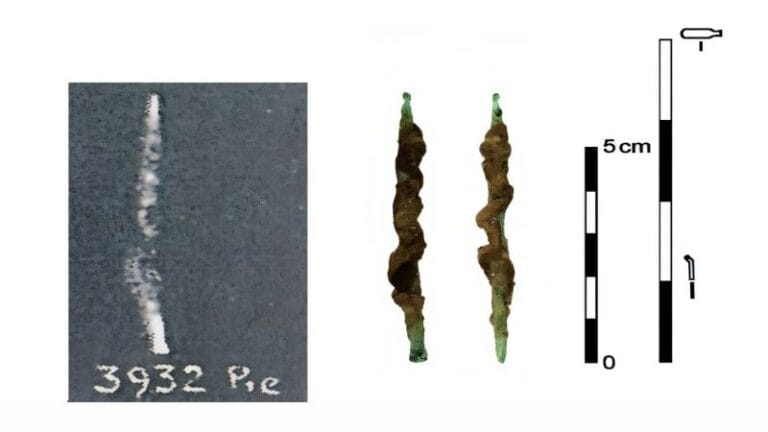

This cremation contained the remains of three individuals and several artifacts of Teotihuacan origin, such as knives, dart points, and green obsidian blades from Pachuca. One of the most notable objects was a carved atlatl point, a weapon characteristic of Teotihuacan warriors. Researchers hypothesize that the main individual cremated was a member of Caracol’s royalty who adopted Central Mexican ritual practices—possibly a Maya emissary who lived in Teotihuacan before returning to the city.

A third burial, discovered in 2009 and also dated to the same period, belonged to a woman. She was buried with four ceramic vessels, a necklace made of spondylus beads, fragments of a mirror, and two Pacific shells.

For the archaeologists, the three burials shed new light on the ties between the Maya and Teotihuacan, decades before the event known as the “Entrada,” recorded in 378 A.D.

“An issue that has intrigued Maya archaeologists since the 1960s is whether a new political order was introduced to the Maya region by Mexicans coming from Teotihuacan,” said Diane Z. Chase, archaeologist and senior vice president of academic affairs at the University of Houston. “Stone monuments, hieroglyphic dates, iconography, and archaeological data suggest that pan-Mesoamerican connections occurred after the event of 378 A.D. known as the Entrada. Whether this event truly represented the presence of Teotihuacanos in the region or the use of Central Mexican symbols by the Maya themselves is still debated. The data from Caracol suggest that the situation was much more complex.”

Arlen F. Chase, professor and chair of the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the same university, highlights the diplomatic role of these contacts:

“Both Central Mexico and the Maya region clearly knew each other’s rituals, as reflected in the cremation at Caracol. Connections between the two regions were maintained by the highest levels of society, suggesting that the early kings of various Maya cities—like Te K’ab Chaak of Caracol—were engaged in formal diplomatic relations with Teotihuacan.”

The dynasty founded by Te K’ab Chaak remained active for more than 460 years, establishing Caracol as an important political center in the Maya lowlands.

Currently, archaeologists continue to analyze the contents of the burial chamber, including the reconstruction of the funerary mask and studies of ancient DNA and stable isotopes. The results of the 2025 excavation season will be presented in August during a conference on Maya–Teotihuacan interaction at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico.