Tools made from whale bones used 20,000 years ago

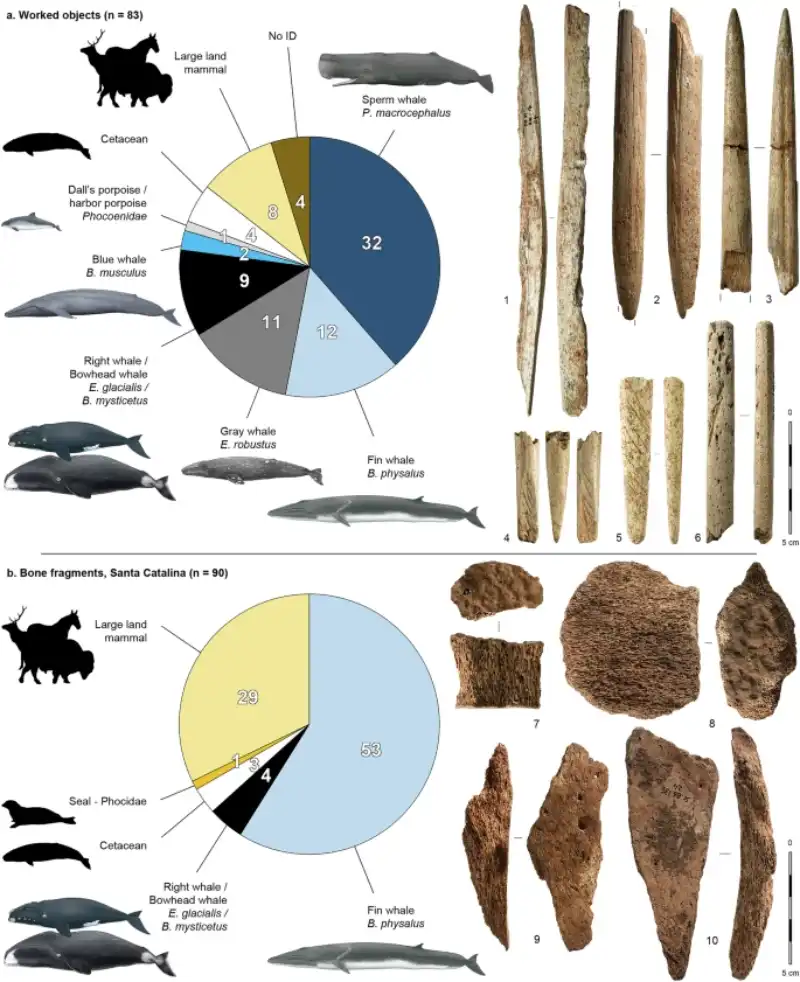

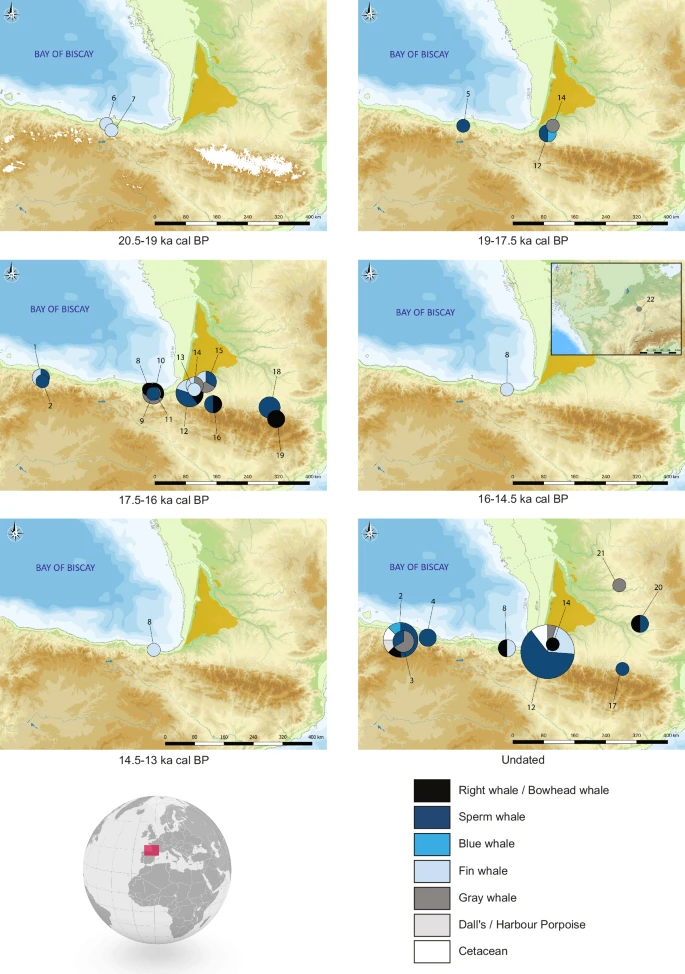

A new study published in Nature Communications reveals surprising evidence of the use of whale bones by Late Paleolithic human groups. Researchers have identified more than 170 fragments – including tools and unworked bones – in archaeological sites located in caves and rock shelters in northern Spain and southwestern France. Dating back between 20,000 and 14,000 years, these materials represent the oldest whalebone artifacts known to date.

The discoveries show that Magdalenian populations took advantage of cetacean strandings and transported parts of their skeletons to areas far from the coast, where these bones were transformed into hunting weapons.

The artifacts were found in places several kilometers from the sea, often in mountainous regions such as the Pyrenees and Cantabria. In particular, in the Santa Catalina cave – located some 70 meters above sea level and 4 to 5 km from the sea – the researchers found unworked bones with human breakage marks.

These transportation logistics suggest a significant effort to take advantage of the resources offered by stranded whales or carcasses carried by currents, turning their bones into raw material for tools.

The team used a technique called ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry) to identify the species from bone collagen. At least six species were recognized: fin whale, sperm whale, grey whale, blue whale, porpoise and a species from the fin whale family (possibly the Greenland or North Atlantic right whale).

This diversity shows that the marine ecosystem of the Bay of Biscay at the end of the last Ice Age was rich and varied, with several species now restricted to the cold waters of the Arctic.

Analysis of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the bones revealed patterns compatible with the current diets of these species: fin and blue whales fed on krill, sperm whales hunted squid in deep waters, gray whales foraged on the seabed and right whales probably fed on copepods.

These data also suggest that, despite climate change since the Pleistocene, some cetacean feeding strategies have changed little – while others may have been influenced by transformations in the environment and the marine food chain.

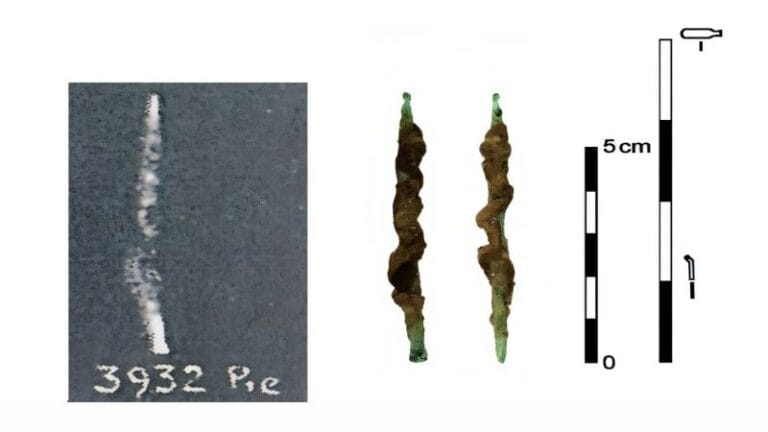

Most of the artifacts identified are projectile tips and foreshafts, i.e. integral parts of hunting weapons. These objects were typologically similar to the traditional tips made from deer antlers, common among Magdalenian groups.

The authors point out that whalebone, due to its size and structural characteristics, offered mechanical advantages – allowing, for example, the manufacture of longer and more resistant spears.

The intensive use of whalebone to make tools peaked between 17,500 and 16,000 years ago. After that, the objects practically disappeared from the archaeological record. The study suggests that this disappearance may be related to the end of exchange and circulation networks between coastal groups and those occupying higher regions, whose archaeological sites are preserved today.

As many of the coastal areas were flooded by rising sea levels over the following millennia, an important part of this history may have been lost.

In the Santa Catalina cave, unworked fragments of very porous bones – some of them with percussion marks – raise the hypothesis that they could have been used as a source of fat or oil. There are also records of whale barnacles at other sites, which indicates that the skin or blubber was also transported and used.

Although only bones remain in the archaeological record, the study suggests that other materials – such as baleen (keratin filtering structures) and meat – may also have been used.

The evidence gathered in this research shows that Magdalenian populations maintained a close relationship with the coastal environment. Even without developed nautical technology or maritime hunting techniques, these communities demonstrated the ability to exploit the resources offered by the coast in a sophisticated and adaptive way.