Why a Gravitational Wave Observatory on the Moon?

Scientists detected the first long-predicted gravitational wave in 2015, and researchers have been eager for better detectors ever since. But Earth is hot and seismically noisy, and this will always limit the effectiveness of Earth-based detectors.

Is the Moon the right place for a new gravitational wave observatory? Could it be. Sending telescopes into space has worked well, and setting up a gravitational wave observatory on the Moon could also work, although the proposal is obviously very complex.

Most astronomy is about light. The better we can detect it, the more we will learn about nature. This is why telescopes like Hubble and JWST are in space. Earth’s atmosphere distorts telescope images and even blocks some light, such as infrared. Space telescopes get around both of these problems and have revolutionized astronomy.

Gravitational waves are not light, but detecting them still requires extreme sensitivity. Just as Earth’s atmosphere can introduce “noise” to telescope observations, Earth’s seismic activity can also cause problems for gravitational wave detectors. The Moon has a big advantage over our dynamic, ever-changing planet: it has much less seismic activity.

Since Apollo times, we have known that the Moon is seismic. But unlike Earth, most of its activity is related to tidal forces and small meteorite impacts. Most of its seismic activity is also weaker and much deeper than Earth’s. This has attracted the attention of researchers developing the Lunar Gravitational-wave Antenna (LGWA).

LGWA developers have written a new paper, “ The Lunar Gravitational-wave Antenna: Mission Studies and Science Case .” The lead author is Parameswaran Ajith, a physicist/astrophysicist at the International Center for Theoretical Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bangalore, India. Ajith is also a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

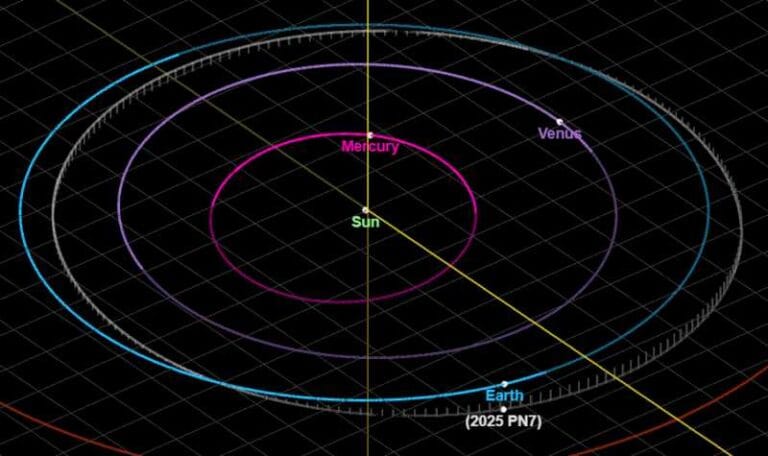

A gravitational wave observatory (GWO) on the Moon would bridge a gap in frequency coverage.

“Given the size of the Moon and the expected noise produced by the lunar seismic background, LGWA would be capable of observing GWs of about 1 mHz to 1 Hz,” the authors write. “This would make LGWA the missing link between space-based detectors like LISA, with peak sensitivities around a few millihertz, and proposed future ground-based detectors like the Einstein Telescope or Cosmic Explorer .”

If built, the LGWA would consist of a planetary-scale array of detectors. The Moon’s unique conditions will allow LGWA to open a larger window into gravitational wave science. The Moon has extremely low background seismic activity, which the authors describe as “seismic silence.” The absence of background noise will enable more sensitive detections.

Detectors need to be supercooled, and the low temperatures in PSRs make this task easier. The LGWA would consist of four detectors in a PSR crater at one of the lunar poles.

The LGWA is an ambitious idea with the potential to change the scientific game. When combined with telescopes that observe the entire electromagnetic spectrum and with neutrino and cosmic ray detectors – called multimessenger astronomy – it could advance our understanding of a range of cosmic events.

LGWA will have some unique capabilities for detecting cosmic explosions. “Only LGWA can observe astrophysical events involving WDs (white dwarfs), such as tidal disruption events (TDEs) and SNe Ia,” explain the authors. They also highlight that only LGWA will be able to warn astronomers weeks or even months in advance about the merger of compact solar-mass binaries, including neutron stars.

LGWA will also be able to detect lighter intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) binaries in the early Universe. IMBHs played a role in the formation of today’s supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the hearts of galaxies like ours. Astrophysicists have many unanswered questions about black holes and how they evolved, and LGWA should help answer some of them.

Double white dwarf (DWD) mergers outside our galaxy are something else that LGWA alone will be able to detect. They can be used to measure the Hubble Constant . Over the decades, scientists have obtained more refined measurements of the Hubble constant, but there are still discrepancies.

LGWA will also tell us more about the Moon. Its seismic observations will reveal the Moon’s internal structure in more detail than ever before. There is a lot that scientists still don’t know about its formation, history and evolution. LGWA’s seismic observations will also illuminate the Moon’s geological processes.

LGWA’s mission is still being developed. Before it can be implemented, scientists need to know more about where they plan to place it. That’s where the Soundcheck preliminary mission comes in.

In 2023, ESA selected Soundcheck in its reserve pool of scientific activities for the Moon . Soundcheck will not only measure surface seismic displacement, magnetic fluctuations and temperature, but it will also be a technology demonstration mission. “Validation of the Soundcheck technology focuses on inertial sensor deployment, mechanics and reading, thermal management, and platform leveling,” the authors explain.

In astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, and related scientific endeavors, we always seem to be on the precipice of new discoveries and a new understanding of the Universe and how we fit into it. The reason it always seems that way is because it is true. Humans are getting better and better at this, and the advent and flowering of GW science exemplifies this, even though we are just getting started. Not even a decade has passed since scientists detected their first GW.

What will be the direction from now on?

“Despite this well-developed roadmap for GW science, it is important to realize that the exploration of our universe through GWs is still in its infancy,” the authors write in their paper. “In addition

to the immense expected impact on astrophysics and cosmology, this field has a high probability of unexpected and fundamental discoveries.”

This article is republished from Universe Today . Read the original article.