How aging affects bone cells

You know that feeling that your body is getting more “stiff” or “creaky” with age? Well — it’s not just your imagination. A new study shows that, just like the rest of the body, the cells in our bones also age, and these changes can weaken the entire structure that supports us.

Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with the Mayo Clinic and the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, have taken an important step toward better understanding this process. The study focused on osteocytes, key cells responsible for maintaining bone health. And what they discovered is revealing: as we age, these cells undergo deep changes that affect both their shape and their function — directly weakening the bones.

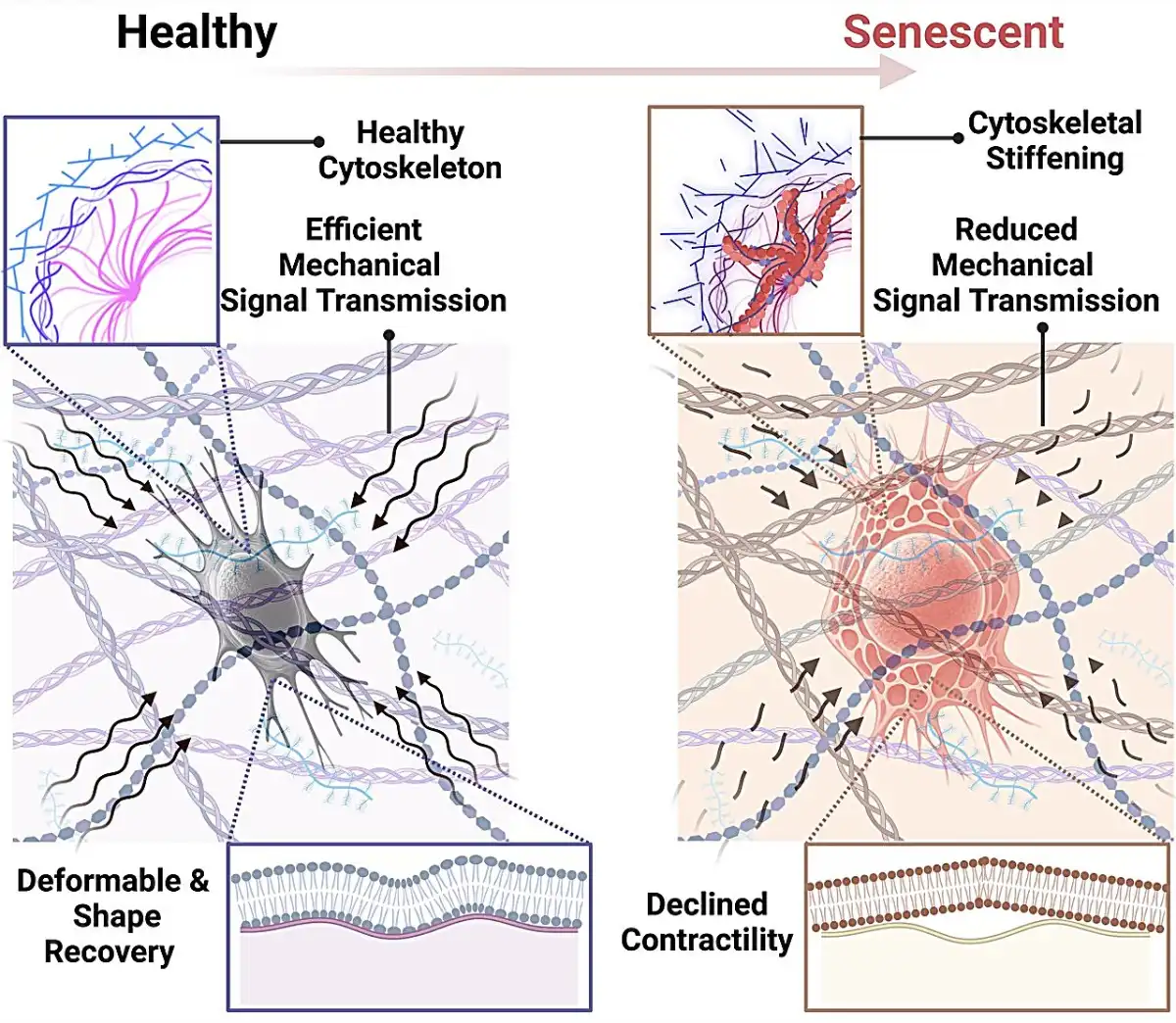

The results, published in the journals Small and Aging Cell, show that aging and stress lead osteocytes into a state called cellular senescence. This means that although these cells remain alive, they stop dividing and become dysfunctional. Even worse: they begin to change physically, becoming stiffer and less responsive to the stimuli that would normally trigger bone renewal.

“Think of the cytoskeleton as the scaffolding of a building,” says Maryam Tilton, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and lead author of the study. “If that scaffolding stiffens, the building loses its ability to adapt to pressure and changes. The same happens with osteocytes: when they become rigid, they stop properly regulating bone health — and that’s when the skeleton starts to deteriorate.”

The problem worsens because these senescent cells also release a set of toxic substances (known as SASP) that cause inflammation and damage the surrounding tissue. This “toxic cocktail” is already known to be linked to several chronic diseases — including cancer.

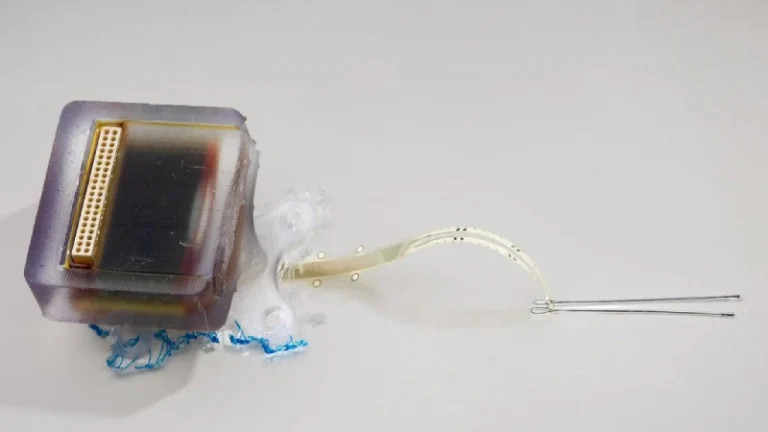

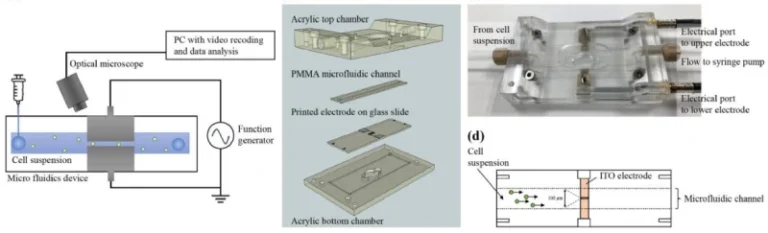

While many previous studies have tried to identify these cells through genetic markers (which vary greatly from cell to cell), Tilton’s team took a different approach: they looked at the mechanics of the cells — how they behave physically. This approach could open the door to new, more precise and effective therapies.

“Just like physical therapy helps stiff joints start working again, we’re exploring whether mechanical stimuli can reverse or selectively eliminate aged cells,” explains Tilton.

This idea is supported by James Kirkland, co-leader of the study and an expert in cellular aging. According to him, understanding the mechanics of osteocytes could not only help detect them more precisely but also enable the development of treatments that eliminate these damaged cells without affecting the healthy ones — something current drugs don’t always manage to do.

This breakthrough is especially important in the fight against osteoporosis, a disease that affects millions of people worldwide and is directly linked to the loss of bone mass over time. With a rapidly aging global population, uncovering how our bones change with age is more than just a scientific curiosity — it’s a public health necessity.

Now, the researchers want to take the study further and understand how different types of stress affect these cells. The hope is that, soon, we will not only be able to treat bone fragility but prevent it before it becomes a real problem.