Discovery reveals the oldest cremation ever recorded in Africa

Researchers have identified, in northern Malawi, what is considered the oldest known cremation on the African continent. The find — a funerary pyre dating back about 9,500 years — points to surprisingly complex mortuary rituals carried out by Stone Age hunter-gatherer groups. The study was published in the journal Science Advances.

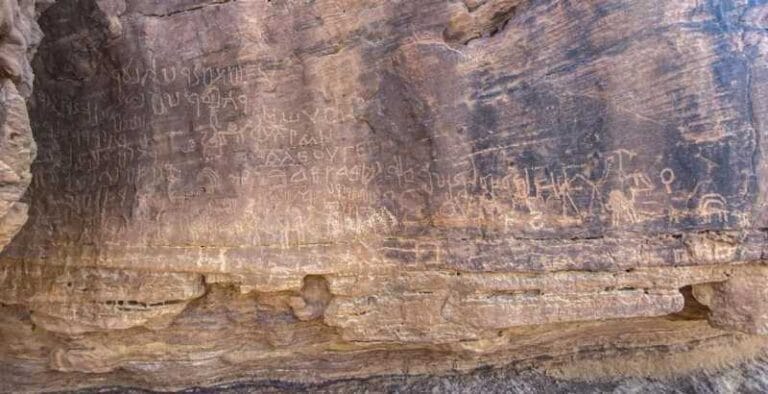

The discovery site is the Hora 1 archaeological site, located beneath a rock shelter at the foot of Mount Hora, a granite inselberg that rises in isolation above the plain. Excavations indicate that the region was inhabited as early as 21,000 years ago and used as a burial area between 16,000 and 8,000 years ago.

Until now, all burials identified at the site were complete inhumations — bodies interred intact in the ground. The newly discovered cremation, however, represents a clear break from that pattern and involved only a single individual.

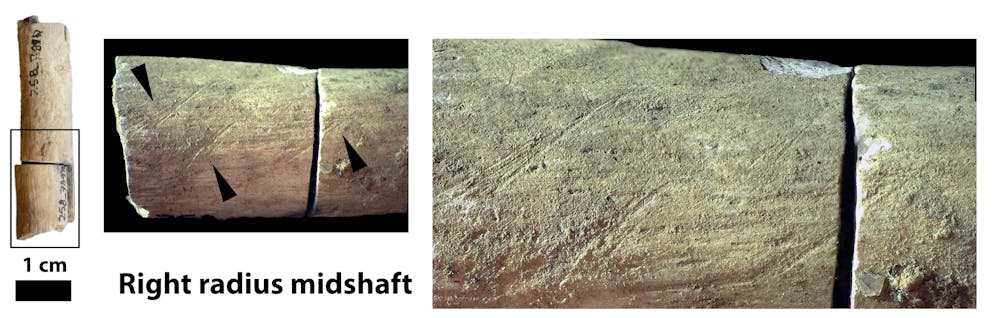

The researchers recovered about 170 fragments of human bone preserved within an extensive layer of ash. Analysis indicates that the remains belonged to a short-statured adult woman, estimated to have been between 18 and 60 years old. Burn marks show that the body was placed on the pyre shortly after death, before decomposition had begun.

In addition, cut marks were identified on bones from the limbs, interpreted as signs of dismemberment or the deliberate removal of soft tissue prior to cremation. The absence of teeth and skull fragments suggests that the head may have been removed beforehand.

The reconstruction of the ritual points to a collective and highly organized event. The archaeologists estimate that at least 30 kilograms of wood and grass were gathered as fuel. Microscopic traces also indicate active control of the fire, with the constant addition of material to maintain temperatures above 500 °C.

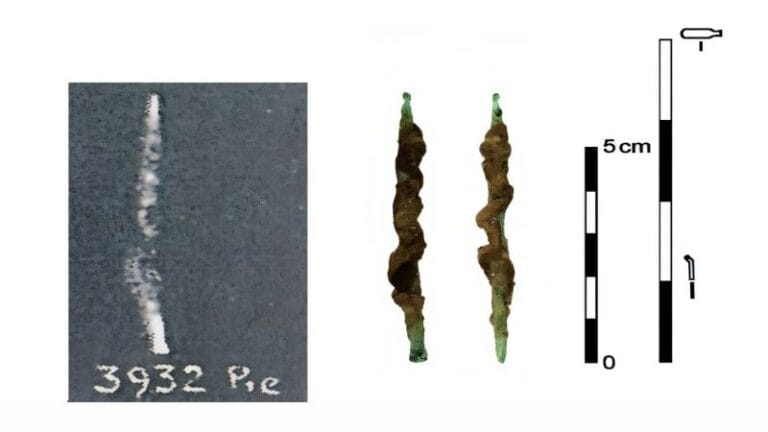

Stone tools found among the ash layers may have been deposited during the ritual as symbolic elements of the ceremony. The study also shows that the same location was used centuries before and after the cremation, with evidence of large fires lit there over time — a sign that the space retained strong collective memory and ritual significance.

Even so, no other similar cremation has been identified in the area, and the reasons why that woman received such a unique treatment remain unknown.

According to the authors, the discovery shows that early African foragers were capable of carrying out elaborate and symbolic funerary practices, combining mastery of fire, community organization, and a strong connection to the landscape — elements not previously associated with hunter-gatherer groups from this period.