Byzantine Monastic Complex Discovered in Upper Egypt Reveals Monks’ Way of Life

The Egyptian archaeological mission affiliated with the Supreme Council of Antiquities, working at the site of Al-Qarya bi-Al-Duweir in the Tama district of Sohag Governorate, has uncovered the remains of a complete residential complex intended for monks, dating to the Byzantine period. The discovery was made as part of ongoing archaeological excavations at the site, where the remains of structures built of mudbrick were identified.

The Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Sherif Fathi, stated that this discovery reflects the richness and diversity of Egypt’s cultural heritage across different historical periods. He also emphasized that such finds strengthen the ministry’s efforts to develop cultural tourism and promote non-traditional archaeological destinations, helping to attract a greater number of visitors and researchers interested in the history of civilizations and religions.

For his part, the Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, stressed the importance of the discovery for providing new information that helps to clarify the nature of monastic life in Upper Egypt during the Byzantine period. According to him, the excavation results indicate the existence of an organized pattern of settlement and daily life within the uncovered buildings, suggesting that they served as residences for an integrated monastic community that lived at the site during that time.

In the same context, Mohamed Abdel-Badie, Head of the Egyptian Antiquities Sector at the Supreme Council of Antiquities, explained that the mission succeeded in uncovering the remains of rectangular-plan buildings constructed of mudbrick, oriented along a west–east axis, with dimensions ranging approximately from 8 × 7 meters to 14 × 8 meters. These buildings include rectangular halls, some containing structures resembling niches or apses intended for worship, as well as several small rooms with vaulted ceilings that were likely used as monks’ cells and spaces for devotion.

He added that the walls of the buildings preserved remnants of plaster layers, with niches and wall openings, while the floors were composed of a plaster layer. Some structures also stand out for the presence of courtyards on the southern side, where the entrances were located, in addition to the remains of small circular structures that were probably used as communal tables for the monks’ meals.

The Director-General of Antiquities in Sohag, Dr. Mohamed Naguib, reported that the excavations also revealed the ruins of tank-like structures built of red brick and limestone, coated with a layer of red plaster, which were likely used for water storage or for industrial activities related to the nature of the site. An adobe building extending from east to west, with approximate dimensions of 14 × 10 meters, was also identified and is believed to have served as the main church of the monastic complex.

The church structure consists of three parts: the nave, the choir, and the sanctuary. In the nave, the remains of mudbrick pillars were found, indicating that it was covered by a central dome. The sanctuary is located at the center of the eastern end, semicircular in shape, and flanked by two side chambers.

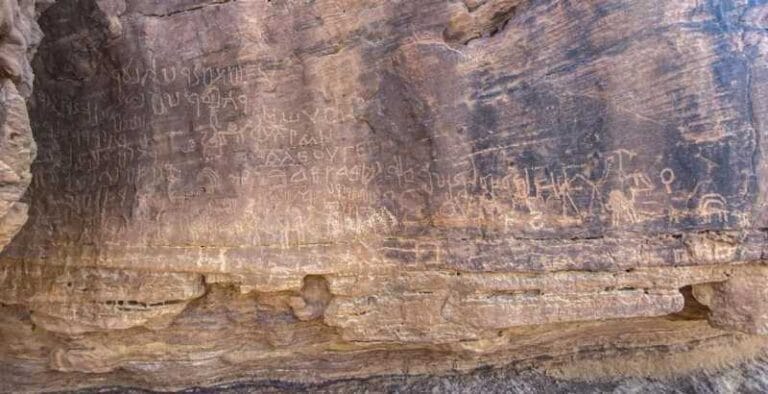

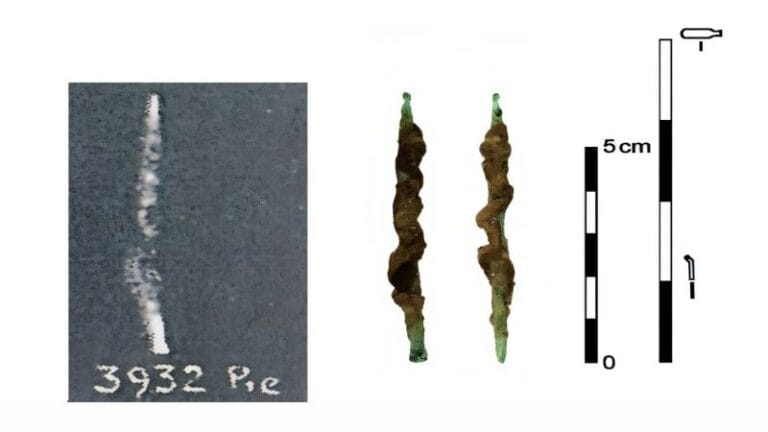

The head of the archaeological mission, Walid El-Sayed, explained that the team found a variety of archaeological artifacts at the site, including amphorae used for storage, some bearing inscriptions that may be letters, numbers, or names engraved on their shoulders. Several ostraca with inscriptions in the Coptic language were also discovered, along with everyday utensils, stone fragments representing parts of architectural elements, and pieces of limestone plaques engraved with inscriptions in Coptic script.